Share this article

Which Sand is Best for Endangered Sea Turtles’ Nests?

Spending the summer peering around a beach in St. Kitts in search of leatherback sea turtles and their nests wasn’t just a walk in the park — or on the beach — for Mark Mitchell and his team of researchers.

One day while conducting their field work, Mitchell, a professor of zoological medicine at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, warned one of his students that sand fleas would be out in full force and offered her his netted hat. She declined his offer, but soon after they began looking for sea turtles, the fleas swarmed. “They were just brutal,” said Mitchell, the senior author of a recent study published in the Journal of Herpetological Medicine and Surgery that looked at how leatherback sea turtles choose their nesting sites. So brutal that they ended up going underneath the netting on his hat, making it hard to focus. “How’s that hat treating you,” said Mitchell’s student, laughing.

Mitchell and his team endured the fleas as they observed some rather disturbing activities: people illegally harvesting eggs and using the beaches where the turtles nest. Leatherbacks — the largest of the sea turtle species that are listed as threatened on the IUCN Red list — choose their beach nesting sites based on the sands’ characteristics. “We wanted to find out if there was anything special about where they laid [their eggs] in regards to the beach itself,” Mitchell said. To do this, he looked at associated characteristics including pH and grain size.

Leatherback sea turtles, which face threats such as illegal sand mining — extracting sand from beaches to use it for manufacturing — and human encroachment through housing and beach usage, usually return to their nesting sites where they lay their clutches every other year. “To find their way back to those beaches is a very impressive thing,” Mitchell said. The team wanted to find out which parts of the beach the sea turtles preferred and how that may affect the populations.

While searching for the leatherbacks throughout the night, the team kept track of air and water temperatures, humidity, wind speed, the lunar phase, cloud cover, the tides, and levels of natural and artificial light. Further, they collected sand in the turtles’ nest sites as well as in control sites and measured the temperature, pH, conductivity, moisture content and grain size of the sand. After reviewing these data, Mitchell and his team found that the sea turtles tend to nest in sand with a slightly higher pH and a milder conductivity than sand in the control sites at the same depth. “They also use more compact sand to build their nest and incubation chambers to put their eggs in,” he said.

Mitchell said the knowledge of how these endangered species choose their nesting sites can be both helpful to researchers and to ecotourism — which could help with the conservation of the leatherback sea turtles.

The focus of ecotourism in the area is to use the money generated by tourists to help finance local fisherman so that they don’t have to fish for sea turtles. “We want to maximize the amount of sea turtles that tourists get to see,” Mitchell said.

Mitchell also said this research will help conservationists know which characteristics of a beach the turtles prefer for nesting. “When protecting sites, it’s helpful to know that turtles have a preference,” he said. “This is just another piece of the puzzle to help with their conservation.” Mitchell continued, “When humans look at a beach, they say ‘look there’s a beach’ but when sea turtles look at a beach, they see nesting sites within that beach.”

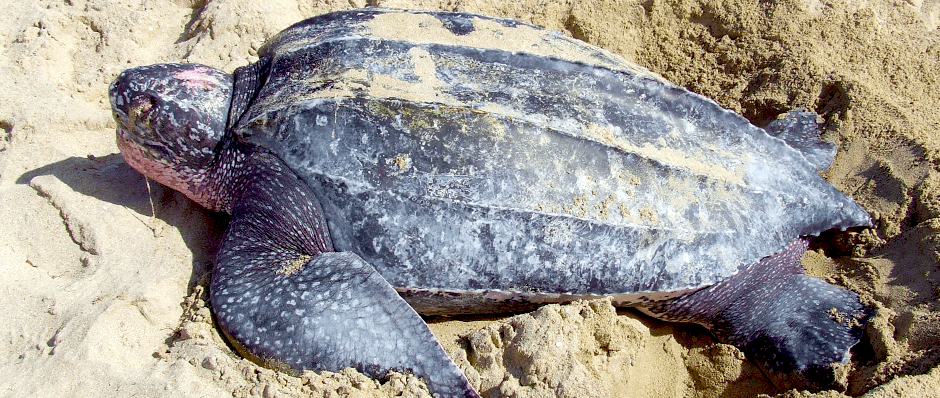

Header Image:

A leatherback sea turtle in the sand at Sandy Point National Wildlife Refuge in the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Image Credit: Al Woodson, licensed by cc 2.0