Share this article

TWS member’s citizen science project tracks a wildlife hazard — balloons

Matthew Bettelheim had seen one too many balloons, deflated and forgotten, lying around in nature. Doing field work in what seemed like remote locations throughout the San Francisco Bay Area, he’d find latex and Mylar balloons, or fragments of them, polluting places where they could pose a threat to wildlife.

Sea kayakers recover a streamer of latex helium balloons celebrating the birth of a child from the waters of Connecticut’s western Long Island Sound. ©2Geeks@3Knots

They may be beautiful when they soar into the sky, but when they come back to earth, they can be deadly, Bettelheim said. Wildlife can mistake them for food. Once a balloon enters an animal’s digestive system, it can reduce food uptake, block the intestinal tract and cause the animal to slowly starve to death. Wildlife can also become tangled in the balloon material or the pretty ribbons attached to them, making them unable to move or feed, leading to stress, injury, malnutrition and eventually death.

It was ironic, Bettelheim thought. California had banned the sale of single-use plastic bags because of the threat they posed to the environment, but Californians were still releasing helium balloons on purpose every day.

“Think of it as deferred littering,” said Bettelheim, a science writer and wildlife biologist at the engineering firm AECOM. A Certified Wildlife Biologist®, he is an active member of the TWS Western Section’s San Francisco Bay Area Chapter.

Bettelheim set out to use citizen science to keep track of the deflated balloons that people came across. He calls it the #mcd project, using a hashtag derived from the maxim “What goes up must come down,” and he has set up a website to promote it. The project encourages the public to use Litterati, a mobile app developed to track and geotag litter. When people find stray balloons, he encourages them to photograph them and tag them in the app using the hashtag #mcd plus either #latexballoon or #mylarballoon. And then, of course, throw them away.

Or, as his website puts it, “Track it down! Tag it up! Pack it out!”

His hope is to create a shared dataset to shed light on the fate of balloons after they’re released outside and give researchers and policy-makers hard numbers to guide them.

Sea kayakers recover a smiley-face balloon on New Year’s Eve, 2015, from the waters of Connecticut’s western Long Island Sound. ©2Geeks@3Knots

Balloons “have staying power,” Bettelheim said. Even latex balloons, which are touted as biodegradable, may take up to 10 weeks when exposed to air, or five months submerged in water, before they break down, he said.

“That leaves plenty of time for wildlife to ingest them,” he said.

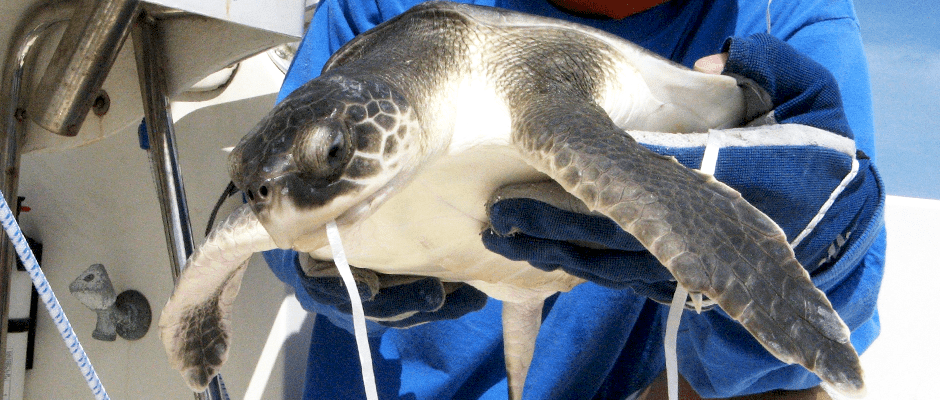

Mylar, or foil, balloons don’t biodegrade, Bettelheim said, and the attached strings and ribbons can ensnare birds, sea turtles, marine mammals, and terrestrial mammals such as bighorn sheep.

Part of the problem, he said, is that deflated balloons can resemble common prey or food, like fruit or flower petals. In one study, balloon fragments were found in 30 percent of sea turtles, which eat a jellyfish that can resemble fractured latex balloons.

Balloon releases are often well-intentioned, Bettelheim said. Sometimes it’s a single child letting loose one balloon. Sometimes it’s a graduating class letting hundreds soar. But in the end, they’re “culturally-approved acts of littering,” he said, “acts that threaten the spotlessness of the outdoors and the wildlife that inhabit them.”

Header Image: A synthetic ribbon trails from the mouth and wraps around the front flippers of a Kemp’s ridley turtle found near Sarasota, Fla. The juvenile turtle had ingested the latex end of a toy balloon. ©Blair Witherington