Share this article

Political instability main factor in waterbird conservation

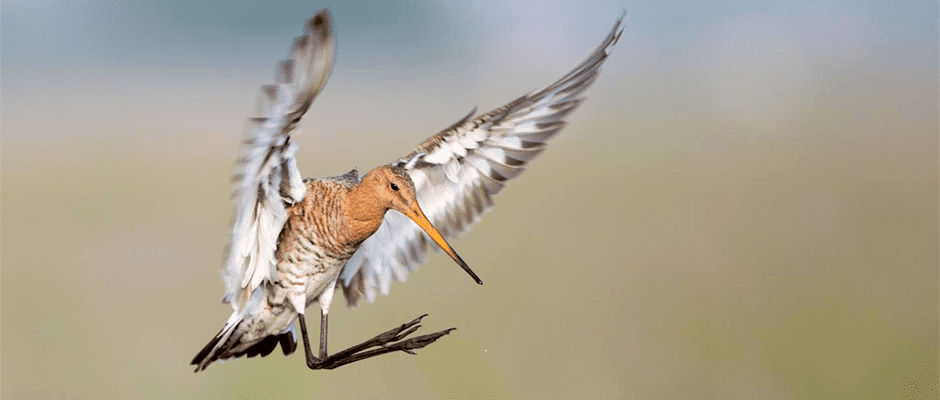

Even more than climate change, human population growth or their own species characteristics, waterbird species across the globe seem to be declining mostly from political instability and weak governance, according to new research.

In a study published in Nature, a research team compiled data on wetland habitats covering about 1.3 billion hectares around the world from the Wetlands International database and the National Audubon Society’s annual Christmas Bird Count.

“The biggest reason for us to focus on waterbirds was the special coverage of this data,” said lead author Tatsuya Amano, a post-doctoral research fellow at the University of Cambridge’s Department of Zoology and Centre for the Study of Existential Risk. “We had the advantage of so many sites in these datasets, including many areas like Africa and western and central Asia where normally there’s very little information about biodiversity change.”

These waterbirds cover a wide range of species, from ducks and geese to flamingoes and pelicans.

After compiling the data, Amano and his colleagues looked at a few predictors of biodiversity and species loss in the areas, including anthropogenic impacts such as agricultural expansion, climate change and human population growth; species characteristics such as body size and migratory status; and conservation efforts such as protected area coverages and governance.

Political instability turned out to be the strongest predictor of species and biodiversity decline.

“Obviously, I knew governance was an important factor in conservation,” Amano said. “To be honest, I didn’t really expect to see governance as the most important factor.”

The researchers found especially large losses in waterbirds in Iran and Turkmenistan, due largely to poor water management and severe hunting pressure. In Europe and North America, waterbird species are generally doing well, Amano said, although some species in these countries are also rapidly declining. The success, Amano said, is because of the successful conservation efforts in these two regions. “But obviously, situations could rapidly change in European countries and in the U.S.,” he said. “If governance will deteriorate in the future, waterbirds might suffer from declines even in these two regions.”

Amano hopes countries take these findings into consideration. While protected areas are expanding globally, Amano said, they may not be enough to conserve imperiled species.

“The study illustrates we should spend conservation efforts on appropriately managing those protected areas as much as establishing new ones,” he said.

Header Image: Waterbirds like the black-tailed godwit (Limosa limosa) face population threats from a variety of sources, but a recent study found political instability and weak governance was one of the greatest predictors of waterbird decline. ©Szabolcs Nagy, Wetlands International