Share this article

Hibernating toads reveal climate change clues

Almost every spring night for nearly 25 years, David Green has visited the dunes of Lake Erie and waited for nocturnal toads to emerge from hibernation. He has waded through the marshes of Ontario, swatting flies and occasionally having to dislodge his car from the sand — all to collect data on the toads.

Green’s student Nicole Sanderson with a Fowler’s toad. Green worked with students to capture toads in order to collect abundance data on the species. ©David Green

Recently, Green, a professor at the Redpath Museum in Quebec’s McGill University, discovered that his long-studied research subjects — the Fowler’s toad (Anaxyrus fowleri) — might be able to offer important clues regarding climate change. As part of a new study published in the journal Global Change Biology, Green reviewed the swaths of hibernation data that he and his students collected over the years to determine how the species is affected by a warming climate.

“A number of species such as the wood frog come out in early spring when it warms up a bit and sometimes there’s still snow on the ground,” Green said. When these species emerge during an early spring, the change in their hibernation patterns is clear, according to Green. However, with late spring breeders such as the Fowler’s toads, it’s more difficult to decipher changes in when they end their hibernation. “We wanted to see if we can predict when they come out of the ground,” he said. Fowler’s toads occur across much of the eastern U.S. as well as in parts of Canada, and their overall population has been declining in the last decade.

By capturing, tagging and releasing hibernating toads for over two decades, Green and his team helped build historical records of the species’ abundance — information that helps shed light on when a significant proportion of the population usually comes out during hibernation. In addition, the researchers also kept track of the temperature, rainfall and snowfall during early spring using records from a nearby weather recording station. After reviewing the data, Green found that the time that the toads emerge from their hibernation can be predicted based on temperature and precipitation. The toads bury themselves in the sand and emerge when the sand below them becomes cooler than the sand above, Green said. However, as the years go on, this is happening earlier and earlier.

Green continues to study the toads and says he wants to “understand this whole system and what’s going on.” For example, his abundance research showed that while it’s normal for the toad population to oscillate in abundance, populations started to decline in 2002 and haven’t recovered since. Green attributes this to an invasive reed phragmites (Phragmites australis) that infests marshes and takes over breeding grounds for the species.

Green plans to continue collecting data on the species and has recently put temperature probes in the dunes. The probes have automatic temperature loggers that determine the ground temperature.

Green hopes the information from the study can help conserve other wildlife species as well. “These animals are becoming, to me, the equivalent of a well-characterized system,” Green said of the toads. “… You can learn a lot more about amphibians in general, and other animal populations, too, by studying these toads.”

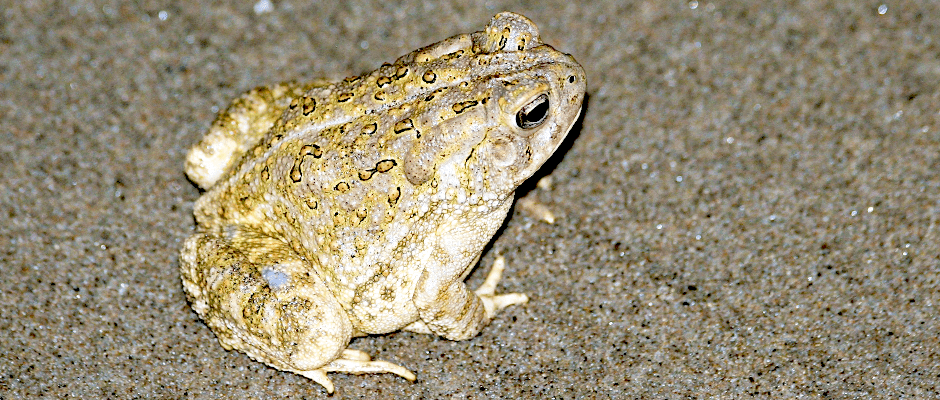

Header Image:

Fowler’s toads hibernate about a meter under the sand for eight months and emerge in late spring.

©David Green