Share this article

Endangered ferrets thrive in their ancestral home

This past September in Meeteetse, Wyoming, biologists panned spotlights over a moonlit prairie dog town. Each flash of emerald eyeshine marked a captive-bred ferret living wild in its ancestral home.

“Once you see ferret eyeshine, it’s very distinctive, because it’s much brighter than anything [else] we’ve got out there,” said Nichole Bjornlie, a biologist with the Wyoming Game and Fish Department and one of the team members who conducted the survey of reintroduced ferrets at Meeteetse.

The surveyors located 19 of the 35 black-footed ferrets released there in July, a relatively high number that suggests the ferrets are doing well. At other reintroduction sites, surveyors have been lucky to find half of the ferrets they originally released, says Bjornlie. While some of the missing ferrets may have perished, others may have traveled to a new site or simply evaded the surveyors’ spotlights.

In the late 1970s, biologists thought black-footed ferrets were extinct. But in 1981, a ranch dog in Meeteetse brought a dead one back to its human family, proving that a remnant population still survived. To save the species, biologists removed all the ferrets from the wild and started a captive breeding program. Now, the multi-agency recovery team has reintroduced ferrets to more than two dozen sites in the U.S., Canada and Mexico, repopulating the species’ former range with the descendants of ferrets from Meeteetse. The release event this past summer marked the first time in three decades that ferrets had set foot on the historic site.

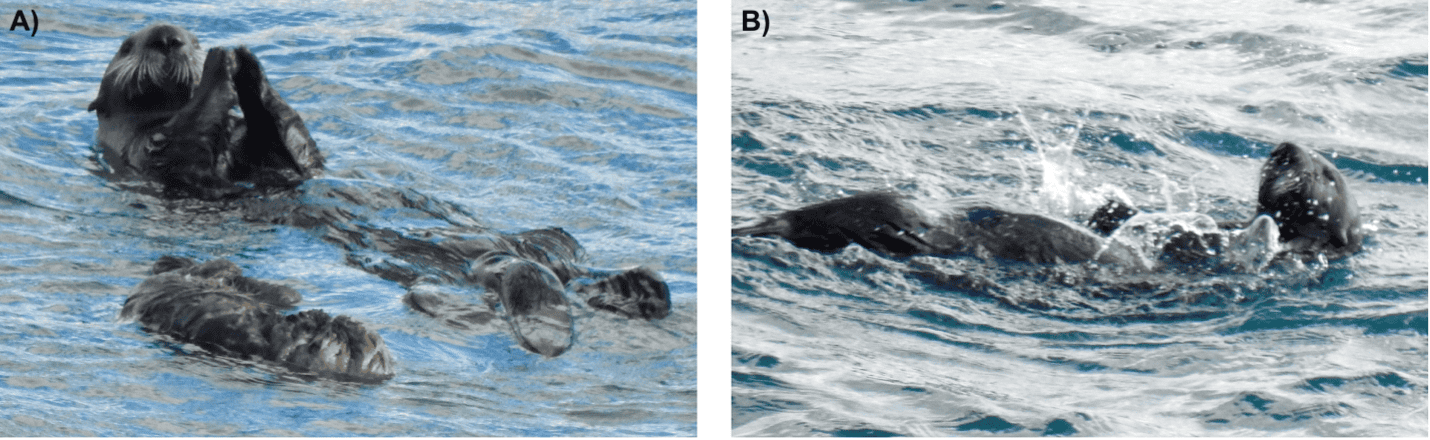

To check on the released animals, the surveyors spent six nights in mid-September searching the prairie dog towns with spotlights. When they saw a ferret’s eyeshine, they watched to see which burrow it disappeared into, then captured it using a trap at the burrow’s entrance. They identified each ferret by scanning its Passive Integrated Transponder tag (the same type of device people use to “microchip” pets), then released it back onto the landscape.

The ferrets haven’t had time to breed yet, so all 19 individuals found during the survey were part of the original release group. But when the biologists return next summer or fall to release more ferrets, they hope to find wild-born kits, says Bjornlie. Each kit they find will receive a PIT tag and vaccinations for distemper and sylvatic plague.

The vaccinations are important, because disease is currently the greatest threat to ferret recovery. In addition to vaccinating ferrets, biologists are using insecticides to kill the fleas that carry plague, and they are working to vaccinate the prairie dogs ferrets feed on. The goal is to establish self-sustaining populations that don’t need to be supplemented with captive-bred animals. The Meeteetse population is in early stages still, but the recent survey suggests it is off to a good start.

“It’s really cool to think that all of those genes that we currently have in ferrets throughout North America are from Meeteetse,” said Bjornlie. “We brought all those genetic contributions back.”

Header Image: A black-footed ferret peers out of a trap during a survey. Surveyors locate ferrets by searching for their distinctive emerald-green eyeshine. [Note: picture wasn’t taken during this particular survey. The description doesn’t give a location.] ©Dan Mulhern