Share this article

California birds adjust nest timing in a warming climate

Birds in California have shifted their breeding season about five to 12 days earlier than a century ago, according to new research.

TWS member Steven Beissinger, a professor of ecology and conservation biology at the University of California, Berkeley, and his colleagues looked back in time to the early 1900s to understand how birds have responded to climate change in the state by comparing detection data collected then to current detection data.

They reviewed notebooks dating back to 1911 from Joseph Grinnell, the first director of the campus’ Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, who logged lists of birds he and his colleagues saw across California.

“As they were collecting specimens, Grinnell was taking copious field notes at all the places they went to record what they saw, serving as an early biodiversity inventory of the state and hoping it would be a great resource for students of the future,” said Beissinger, coauthor of the study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Starting in 2005 Beissinger and his colleagues, as part of the Grinnell Resurvey Project, began revisiting places throughout the state where Grinnell and his students recorded birds and mammals in their notebooks, including the Central Valley and Yosemite National Park. They wanted to find out how factors like climate change and land use change might have affected birds in the same areas today.

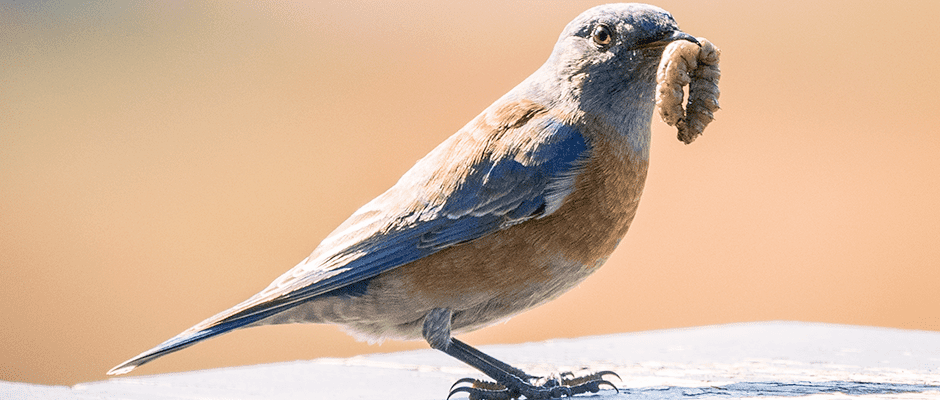

They tallied detections, often singing birds, of species such as mountain bluebirds (Sialia currucoides), western bluebirds (Sialia mexicana) and American robins (Turdus migratorius), that indicated when they began to breed.

“We expected species were responding to climate warming by breeding earlier, and that we would have a greater probability of detecting them earlier in the season,” Beissinger said.

This is exactly what they found. The team saw a shift forward of about nine days on average, corresponding with a 1-degree Celsius temperature rise over the last century.

“By breeding nine days earlier, birds are moving their schedules forward to nest at a temperature similar to what they experienced in the early 1900s,” he said, suggesting the birds may shift timing to stay in the same thermal niche, not just to follow resources.

The good news, Beissinger said, is that these time shifts may allow species to avoid moving geographically, but he worries it may not be enough to keep up with the fast pace of climate change.

“We don’t know if this strategy is going to be a permanent solution or a Band-Aid,” he said.

The team also looked at nest success using the citizen science database Project Nest Watch at Cornell’s Lab of Ornithology. They found that warmer conditions led to more nest failures in southern, warmer regions of species’ ranges, but they resulted in higher nest success in cooler, northern regions.

Overall, Beissinger suggests managers maintain connectivity among habitats so that species have options available to move upslope, or to stay in their habitat and breed earlier.

The Grinnell Resurvey Project is continuing to resample birds and mammals across the state, currently in the deserts of Death Valley National Park, Mojave National Preserve and Joshua Tree National Park.

“We have the opportunity to use the historical data that are available to us and have been preserved in these notebooks,” he said. “Right now, it’s a critical time in climate change and climate history. It’s equally important for us to conserve our data for the students of the future.”

Header Image: A western bluebird holds a caterpillar in its beak in California. © Becky Matsubara