Share this article

Bison size shrinking as temperatures rise

When Jeff Martin was growing up on a bison (Bison bison) ranch, he noticed the bison surrounding him were much smaller than the ones he saw in ice age dioramas at museums.

“I was trying to figure out just why,” said Martin, a PhD candidate and graduate assistant at Texas A&M University and a TWS member. “This led me to document the past and what the relationship was related to today’s bison, to predict what future bison might look like.”

Martin led a recent study published in Ecology and Evolution looking at information from bison fossils dating back to 40,000 years ago and comparing the body sizes and temperatures during those times.

Martin and co-author Jim Mead, the director of The Mammoth Site, in South Dakota, visited museums and their vertebrate paleontology collections and took measurements of the bison’s heel bones. Then, they shared information with researchers at conferences who had taken similar measurements of bison bones and included that information in the study.

“All of those come from about 60 fossil sites that were well-dated chronologically with radiocarbon dating so we have a really good idea of when they were the size that they were,” he said. The 60 sites also give a rough estimate of the geographic coverage of fossil sites from across the Great Plains of North America, which coincidentally is also the primary distribution of bison today.

The team then used Greenland Ice Sheet Temperature Data to determine temperatures at the time the bison were living. As temperatures cooled, researchers found, bison got bigger. “And more important for today, bison get smaller with warmer temperatures,” Martin said, noting climate models predicting warming temperatures in the future.

But while the team knows bison size and temperature are correlated — each 1-degree Celsius bump correlates with a 41-kilogram drop — they don’t yet know the underlying mechanism behind the shrinking bison size.

“We answered the question that they are actually getting smaller, and it is related to temperature at a continental scale,” said Perry Barboza, a professor in the Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences at Texas A&M and Boone and Crockett Chair of Wildlife Conservation and Policy, who co-authored the study. “The question then becomes, so what is happening at smaller scales?”

They wonder if it has something to do with food supply changes as a result of temperature or other mechanisms.

Smaller bison will likely negatively impact the bison populations, researchers believe. Smaller animals reproduce more slowly, possibly reducing populations, Barboza said, and lower population numbers can make the species more vulnerable to impacts such as diseases and predation.

Once the underlying mechanism is determined, Barboza said, managers could determine how to adjust harvest or expand lands and target densities for the bison.

“We have described the phenomena,” Barboza said. “The next step is determining the predominant mechanism. We can then see the possible solutions we can apply. The next step after that is, how can we take those solutions and put them into policy?”

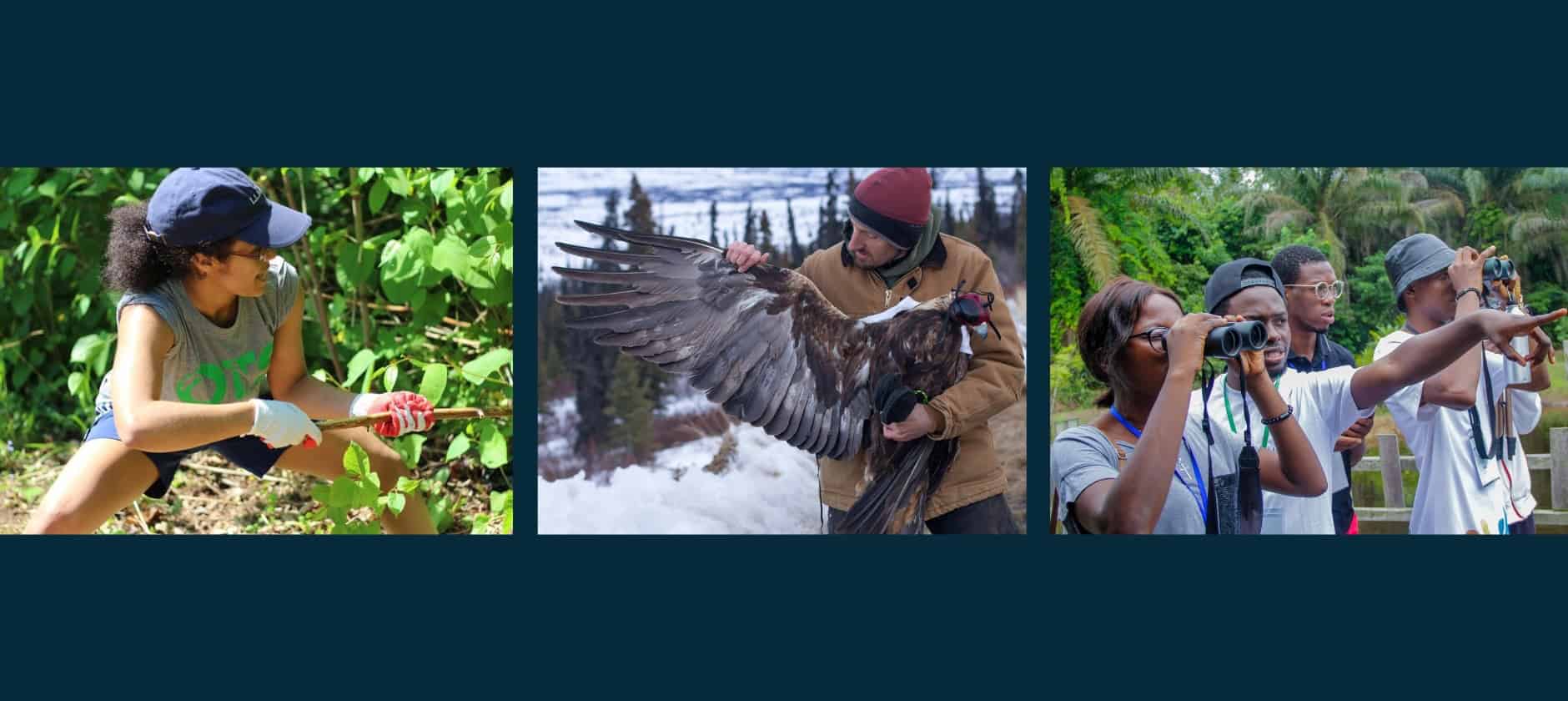

Header Image: Why is this British Columbia bison smaller than its ancestors? Researchers found a link between a warming climate and smaller bison. ©Jim Handcock