Share this article

Bat Maps Help Conservation in Pacific Northwest

Following an eight-year study of bats in the Pacific Northwest of the United States, researchers were recently able to create a new generation of range maps that will help with their conservation in the region, and that with expanded investment in monitoring they hope can eventually be applied throughout North America.

The recent study published in the journal Diversity and Distributions that presents these maps was one of the outcomes of a regional effort called the Bat Grid, according to Tom Rodhouse, an ecologist at the inventory and monitoring program at the National Park Service and lead author of the study. Through the Bat Grid, a collaboration between agencies and state organizations that began in the early 2000s, researchers carefully surveyed different bat species using acoustic detectors, mist nets, and genetic techniques. “The program used a multimethod approach to address different questions,” said Rodhouse, a member of The Wildlife Society. “The one we tackled here was trying to develop predictive distribution models and maps at unprecedented regional scales.”

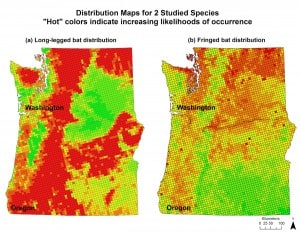

The publicly accessible maps display ranges for 11 bat species across Oregon and Washington states and highlight population trends and habitat features that influence these trends. The maps describe baseline probabilities of occurrence for the bats that can be updated over time to assess the impacts of wind energy development, climate change, and white nose syndrome.

Rodhouse and his team also developed accompanying prediction error maps that addressed the uncertainty of the trends that were displayed. “This is an important step forward in using models to guide decision making and conservation,” Rodhouse said. “Oftentimes, uncertainty can be quite high but is rarely mapped. This will help improve our monitoring of bats, and uncertainty will taper as information is gained over time.”

Distribution maps of two species Rodhouse and his colleagues studied in Oregon. Image Courtesy: Tom Rodhouse

One species that Rodhouse and his team studied was the long-legged myotis (Myotis volans). Through past telemetry studies, the researchers knew that these bats rely heavily on dead tree snags to raise their pups. “They roost under bark at a particular stage of decay,” he said. “When the tree isn’t in the correct stage, it’s no longer useful for the species.” Rodhouse said the supply of these snags, which he calls “keystone structures,” had previously never been shown to be so important on a landscape scale. In their maps, the team found that the distribution patterns of the long-legged myotis and four other species were strongly influenced by the pattern of snag abundance. “This is really important information for land managers. Snag retention as a forest management practice is a straightforward way to do bat conservation,” he said.

Rodhouse and his colleagues also studied the fringed myotis (Myotis thysanodes), a species that’s not widely understood and is hard to study because the bats are rare to find in their range. “We’re revealing what other studies suggest are conservation concerns but have been under the radar,” he said. “We think our maps help advance that conservation and point to species that really need a closer look.”

Rodhouse and his colleagues look forward to updating these “statistically dynamic” maps as new monitoring data rolls in. Normal range maps are just an outline, he said. “They give a false impression that we know more than we do. They also suggest that the animals are fixed in space and time.” However, Rodhouse’s maps use probability, which he acknowledged can be awkward for some audiences, but is much more realistic and can better help guide conservation efforts for these ever-changing populations.

Rodhouse is planning a webinar for regional biologists in December to discuss how the maps can be translated into conservation tools. This study was also the foundation for an initiative called the North American Bat Program (NABat), which will monitor bat distributions across the continent.

“It is important to keep in mind that bats are so hard to survey that pulling off something like this across such a large area is truly unprecedented,” Rodhouse said. “There simply aren’t other datasets and mapping efforts like this anywhere in the world for bats.” Rodhouse and his colleagues recently made their first proposal for how to scale up the coordinated continental bat monitoring. “[It’s] pretty ambitious but we think we can pull it off, and it’s gaining momentum!” he said. “Hopefully this work can help motivate additional investments.”

Header Image: Researcher Tom Rodhouse stands in a cave and looks at a long-eared myotis.

Image Credit: Michael Durham