Share this article

Wildlife Vocalizations: Diana Hallett

Wildlife Vocalizations is a collection of short personal perspectives from people in the field of wildlife sciences.

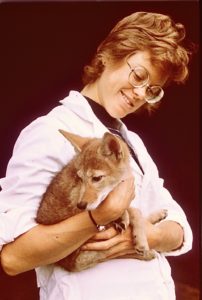

Hallett holds a juvenile coyote in 1974. Twelve coyote pups dug from dens were raised to develop an expandable radio-collar. Funding from Predator Research Facility, Millville, Utah.

Credit: Courtesy of Diana Hallett

I was pursuing a different career path when I took an elective course entitled “wildlife, ecology and man” in 1972. In thisclass, a guest speaker named R. D. Sparrowe piqued my curiosity about wildlife conservation. I entered fisheries and wildlife biology as a non-degree graduate student because I lacked several prerequisite undergraduate credits. I had a steep learning curve. My graduate advisor, T.S.Baskett, then editor of The Journal of Wildlife Management, counseled me to observe, participate and listen in order to increase my understanding of resource science. As a novice, I volunteered to accompany every fisheries and wildlife graduate on fieldwork. I acquired techniques and made friends. I joined The Wildlife Society, learning the rich history of resource management in our nation. As a fledgling biologist, members of TWS provided me with technical assistance and gave me a firm footing in resource management. I found lifelong friends, developed lasting professional relationships, and learned leadership skills. I am indebted to all TWS council members with whom I served for encouraging me. Today, TWS encourages resource professionals to be connected globally. Our current resource challenges require our connectivity.

Out of the observe, be active and listen missives, the best advice that I received was “be a good listener.” As a newly minted wildlife biologist working for the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, I kept my ears open. Often out of my element, I relied on hearing to guide me in fieldwork, meetings and professional relationships. In time, by listening, I learned that sometimes words unsaid proved to be more important than those uttered. Reading between the lines helped me understand preconceived notions. Women were not numerous in the field in the ’70s and ’80s and hearing derogatory words made for challenging times. Being able to listen without reaction or with a laugh often defrayed uncomfortable situations. Within groups (eg. committees, board meetings, public hearings) in order to reach objectives, there is a give and take scenario. Careful listening can reduce conflicts and speed the consensus process. Careful listening instills trust and may shorten negotiation timelines. Careful listening reduces misconstrued expectations. By hearing the correct message, you don’t get diverted. Careful listening allows all sides to be heard. As a leader, careful listening empowers others—the best results are self-directed.

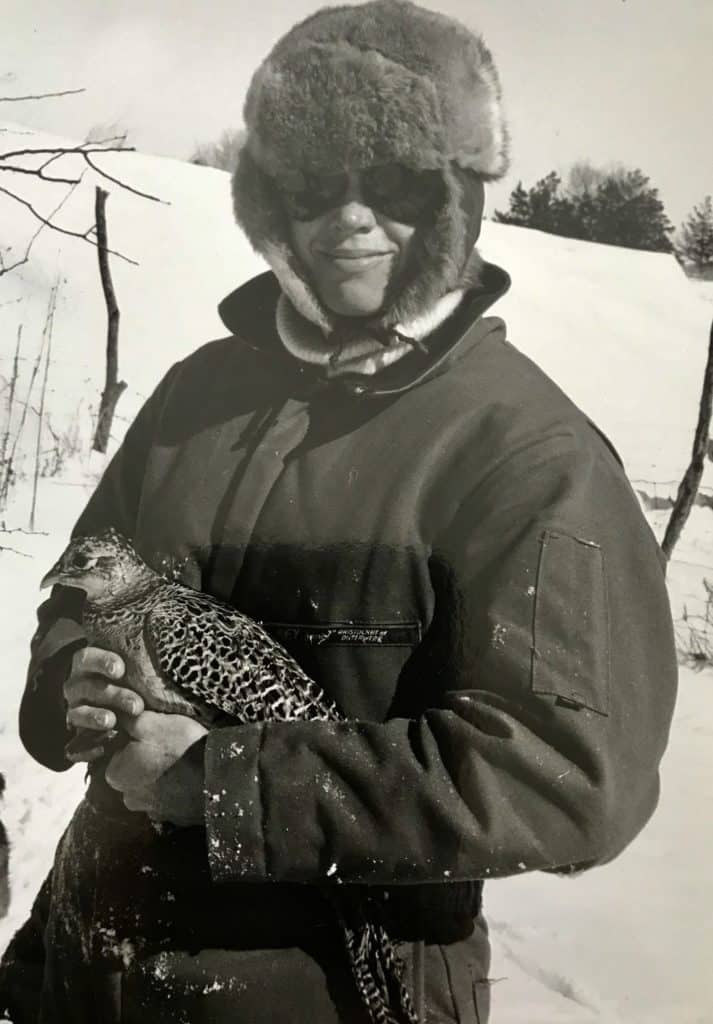

Hallett holds a radio-tagged ring-necked pheasant in 1980 in Scotland County, Missouri. Missouri Department of Conservation telemetry project to track relocated birds from Iowa. Credit: Nancy Lamb

Diana Hallett, Retired Wildlife Research Biologist. Credit: Courtesy of Diana Hallett

After nearly 30 years working for the Missouri Department of Conservation, I retired. I continue to use my listening skills. My husband and I rely upon current Missouri Cooperative Fisheries and Wildlife Unit Leaders, Craig Paukert and Lisa Webb, to guide us in selecting a deserving natural resource graduate student for a fellowship. It is exciting to meet energetic, emerging resource professionals ready to tackle today’s challenges. Membership in TWS has grown in several decades because our organization has demonstrated that our mission remains vital in today’s world. Let us continue to grow.

Learn more about Wildlife Vocalizations, and read other contributions.

Submit your story for Wildlife Vocalizations or share the submission form with your peers and colleagues to encourage them to share their story.

For questions, please contact Jamila Blake.

Header Image: Credit: Courtesy of Diana Hallett