Sodium Nitrite as a toxicant for feral swine?

Many of you may have heard something about this and others are probably thinking; isn’t that a meat preservative? The answer is yes to both. Sodium Nitrite is on the horizon as a “possible” feral swine toxicant. I have been working on an analysis of this project over the past year and thought it may be of interest to some NE TWS members. Although feral swine are no longer an issue in Nebraska thanks to the cooperative efforts of USDA Wildlife Services and Nebraska Game and Parks over the past 10 years or so to eradicate any populations that materialized in the state, they are still a big concern for many surrounding states. I was heavily involved with the eradication efforts in Nebraska while still working as a biologist in Kansas. Many of you probably remember the population of feral swine that established themselves at Harlan County reservoir several years ago. That population was also shared with Kansas and so it became a two state, multi-agency successful eradication effort. I later transferred jobs and moved to Nebraska as a district supervisor for Wildlife Services in 2010.

After a six year tenure as the district supervisor for the Nebraska Wildlife Services program, I accepted a new position with our National program as an Environmental Coordinator for Wildlife Services National Feral Swine Damage Management Program. The new position was an easy transition for me because of my prior feral pig experience in Kansas (best of all, I get to continue working from Ogallala, NE). As an Environmental Coordinator for the feral swine program, I am responsible for assuring that all the states conducting feral swine control/or research are compliant with NEPA (National Environmental Policy Act). My first assignment has been to analyze the potential environmental impacts of a proposed field study to test the effectiveness of sodium nitrite as a toxicant bait for feral swine.

Obviously folks naturally raise their eyebrows when there is talk of a large vertebrate pesticide on the horizon and for good reason. The massive poisoning campaigns for predator control that took place in this country over 50 years ago were short sighted and proved to be detrimental to many wildlife species and were ultimately banned by the Nixon administration in 1972. The fact that we have not seen a large vertebrate pesticide in this country in 45 years makes this a pretty big deal. I saw one reference that said this is the first new vertebrate pesticide in the world in 30 years.

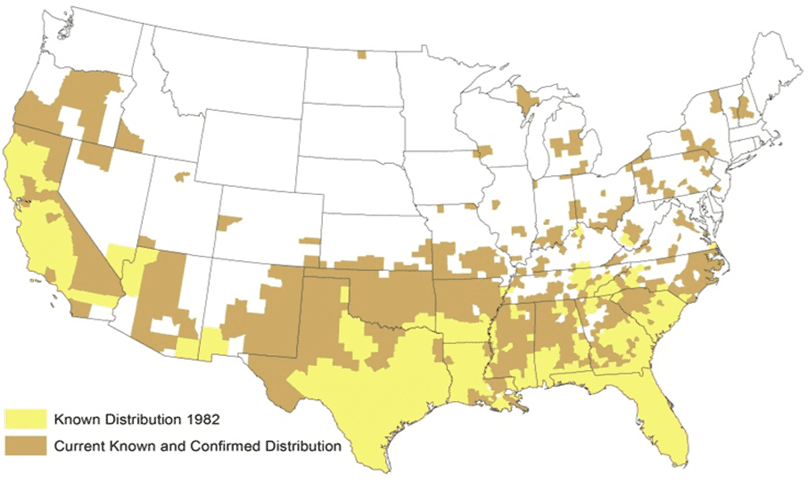

Fortunately, this proposed toxicant is showing some real promise in pen trials to be an effective, potentially environmentally safe product. The product has been field tested in Australia for several years and is currently going through the registration process there. The only place it is currently registered and being used is in New Zealand. Field trials in the U.S. are currently being proposed in an Environmental Assessment and if studies continue and achieve positive results, it is anticipated that a product could be registered for use in 2020-2021. You may be asking, why do we need this? Take one look at the map I provided and you can see that pigs have expanded from a population of about 2 million animals in 17 states to an estimated 6 million animals in 38 states all in about the last 35 years. Current damage estimates suggest that pigs average about $300/animal/year which indicate that annual damages now exceed 1.8 billion dollars.

Current control measures have been effective in some areas but overall, pig numbers continue to increase. We don’t know how effective the addition of a toxicant could be to help control pig numbers and that is one of the primary reasons for the research. The other primary reason for the research is to take a hard look at the non-target and secondary toxicity issues with sodium nitrite.

Non-target, threatened and endangered species and human health and safety are the first issues that come to mind when discussing a toxicant. However, sodium nitrite is vastly different from other toxicants in that there is virtually no secondary residues in the tissues of dead pigs after succumbing to an overdose of sodium nitrite. To give you an example of what I mean when I say “virtually no residue” we found average residues in the muscle to be 3.2 mg/kg. By comparison, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration regulates that no more than 200 mg/kg of sodium nitrite can be used in preserved meat products for human consumption.

How does it work? Sodium nitrite causes direct impacts on hemoglobin. Hemoglobin is a protein in blood responsible for transporting oxygen throughout the body. Sodium nitrite converts hemoglobin to methemoglobin (MtHb). Higher than normal levels of nitrite leads to methemoglobinemia which quickly leads to loss of consciousness and then death from the rapid depletion of oxygen to the brain and vital organs. The severity of methemoglobinemia depends on the balance between MtHb formation and its reduction or reversal back to hemoglobin by a protective enzyme called MtHb reductase. This naturally occurring enzyme catalyzes the reduction of MtHb back to hemoglobin to protect red blood cells against oxidative damage.

Different species have varying levels of the enzyme MtHb reductase resulting in varying levels of sensitivity to sodium nitrite. Feral swine have relatively low levels of the enzyme and so they are susceptible to nitrite-induced methemoglobinemia. Interestingly, species can be tested for sensitivity to nitrite by measuring the levels of the enzyme without actually exposing them to nitrite.

Due to this process, even if pigs were to eat a sub-lethal dose of sodium nitrite, the nitrite is quickly metabolized by the MtHb reductase enzyme and there is no effect to the pig. I guess that is the same reason I can eat a half a pound of bacon for breakfast with no effects! Seriously though, it is the same process. Even animals with relativity low levels of the enzyme can still eat some nitrite with no side effects if they only eat small amounts or eat it slow enough to allow the enzyme to convert oxygen back to the hemoglobin faster than it can be depleted.

For example, in a pen trial in Texas, turkey vultures were fed the stomachs and intestines of sodium nitrite dosed pigs (at one and half times the lethal dose for pigs, 600 mg/kg). The sodium nitrite concentrations in the stomach and intestine tissues were well above what would have been lethal to vultures. They consumed almost the entire contents and showed no adverse effects. The hypothesis is that despite there being lethal concentrations of sodium nitrite in the stomach and intestines, vultures could not eat them fast enough to show any ill effects of nitrite, in other words, the enzyme reversed the effects faster than vultures could consume any lethal dose.

Why does it work for pigs? Well, pigs will be pigs, it’s a double whammy for them, they have relatively low levels of the enzyme and they typically like to eat fast! There are still many variables and challenges to work out such as a species specific delivery devise (also part of the field trial research) that I did not expand on in this article. If I peaked your interest and you would like to read more, click on this short SN fact sheet that we developed and if you are still really interested in the project, click on this Environmental Assessment link to read the full field trial assessment.