Share this article

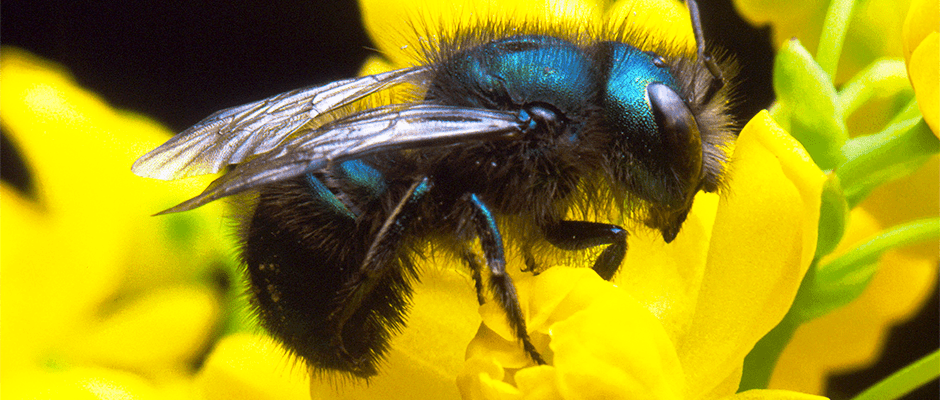

Climate change threatens Arizona’s mason bees

Mason bees are critical pollinators in the high deserts of Arizona, but climate change may drive them out of these and other warm regions as temperatures climb.

“They might be small but these bees pack a big punch,” said Paul CaraDonna, an assistant professor at Northwestern University and a research scientist at the Chicago Botanical Garden. “Pollinators are a big part of making our ecosystems healthy. You start pulling away more and more and you start having a potentially severe effect.”

CaraDonna led a two-year field experiment warming up artificial nests of a species sometimes called the blueberry mason bee (Osmia ribifloris) in Arizona’s Catalina Mountains near Tucson. The bees thrive there, but the area represents the warmest extreme of their range, which extends throughout much of the West, including the mountains of New Mexico, Utah, California and northern Mexico.

In a field experiment simulating a warmer climate future, the team found 35 percent of the bees died in the first year and 70 percent died in the second year, compared to a mortality rate of less than 2 percent in the control group.

“These results were more sobering than I would have expected,” said CaraDonna, lead author of the study published in the journal Functional Ecology.

The mean daily temperature change was on average only about 2 to 2.5 degrees Celsius warmer, representing projected temperatures in the region about 40 years in the future CaraDonna said, “but it was enough to really push this bee up against its physical limits.”

CaraDonna’s team set up 90 nests under three different temperature conditions, representing past, present and future climates. These artificial nests mimicked the holes and cracks in dead tree stumps the bees choose for nesting.

A third of the nests were painted black to absorb more heat, simulating the climate predicted for the years 2040 to 2099. Another third was painted white, to cool the nests to temperatures they would have experienced sometime around the 1950s. A control group was painted with transparent paint.

The rising temperatures affected the bees in the warmer nests in various ways. They emerged later from their insect hibernation — or diapause — than those in cooler nests, which emerged in early February, as they do naturally in the region. The warmer bees also emerged over a much longer period of time than the other bees. And they emerged smaller and with lower fat reserves.

All those factors, alongside the increased mortality, raise questions about the bee’s ability to survive climate change, CaraDonna said. “Unless these bees can rapidly adapt in the next century, they are likely to face some steep challenges,” CaraDonna said.

That could have broader impacts for the ecosystem at large. The bees are major pollinators of the manzanita shrub, an important plant species in these high desert landscapes that affects other organisms that rely on it.

“You take that out and it’s not easy to predict what will happen,” he said.

Header Image: Warmer temperatures increased mortality for mason bees in Arizona. ©Jack Dykinga