Share this article

TWS member solves mountain lion mysteries

This article originally appears in the University of Montana Student Chapter of The Wildlife Society September/October 2018 newsletter.

TWS member Jennifer Feltner doesn’t dress like a stereotypical, wildlife biology grad student, wearing Carhartt pants or a flannel shirt smeared with fieldwork-derived grime. Her stylish, textured crop sweater hangs over a black tank top. Golden elk-antler-shaped earrings catch the light in front of short brunette hair gathered in a spiky ponytail at the back of her neck.

She didn’t take the typical path to get to a wildlife PhD either. Feltner got a degree in Chinese literature, and spent time working in international relations before she decided she’d rather be paid to do her hobbies — hike and track wildlife in the woods.

Now she serves as a kind of wildlife forensic examiner through her PhD fieldwork in conjunction with the Teton Cougar Project — finding kill scenes and figuring out the “whodunnit.” Her goal is to discern what effect recovering large carnivores like wolves and grizzly bears are having on mountain lions in the southern Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem as they expand in population size and range since their reestablishment in the 1990s.

Mountain lions can’t compete with the strength in numbers that wolves have, or with the size advantage of a bear. They have to alter their behavior to avoid getting hurt or killed by these dominate predators. Mountain lions also have to fight “kleptoparasitism” where a dominate predator steals a kill by chasing off a subordinate predator. The dominate predator gets all of the food, wastes none of the effort and the lion goes hungry.

The ways in which mountain lions are shifting their behavior in response to other large carnivores likely impacts mountain lion populations, as well as populations of prey species shared by wolves, bears and mountain lions, such as elk. Feltner hopes to explain and quantify the effects.

For her project, she’s had to overcome a number of challenges. She spent a lot of time hiking through all sorts of difficult conditions to find concentrations of GPS points where her collared lions were hanging around. These areas are known as “clusters.”

Her fieldwork took her to some dangerous cliffs and rough terrain favored by mountain lions. “I learned the hard way a couple of times that cougars can get to places that no human should go without special equipment,” she said.

In her last field season she investigated 1,250 clusters and found 450 kills, 70 instances of food stealing, about 800 cougar beds and four cougar dens. “If you want to do this, I hope you really enjoy the outdoors, hiking and leg workouts,” she says, as she shared her experiences with the student chapter at a recent Tuesday meeting.

Feltner’s advisor wanted her to go to as many of these GPS clusters as possible, and find out what was going on. The ability to track and read sign was essential to Feltner’s ability to look at her mountain lion “crime scene” and determine what happened. Before she started the project, she thought she was a decent tracker, but she was soon shown how much she had to learn. “I really realized how much more clearly you can read a landscape and understand what’s going on with your study species,” she said.

Feltner worked hard to improve her tracking abilities, and has since become a master tracker. She is level three CyberTracker certified. Scoring a level three on this online tracking certification program was very gratifying. “That’s one of the things I’m actually really proud about in my PhD,” she said.

She had to learn to keep an open mind to determine what was happening at a scene when she arrived. Sometimes she found things she never expected. Once she thought for sure she was going to a kill, but found three newborn kittens mewing at her instead. She’s also found unusual prey. A robin, a mountain blue bird, Sandhill cranes, a great horned owl, a chipmunk, and even juvenile mountain lion all found their end at the claws and teeth of some of her study subjects.

If she does find a kill, she can tell what kind of animal made it by looking at signs. If it’s a buried kill or the ribcage was opened and hair was sliced off the animal with sharp teeth, a mountain lion made it. If blood and guts are everywhere or there’s scat around the carcass, a wolf probably brought the animal down.

She was able to determine that bears were the most common kleptoparasites for mountain lions, while wolves sometimes killed mountain lion kittens, important information for understanding predator dynamics.

Feltner closed her presentation by showing beautifully filmed videos on an adapted GoPro camera of a female mountain lion and her yearling kitten.

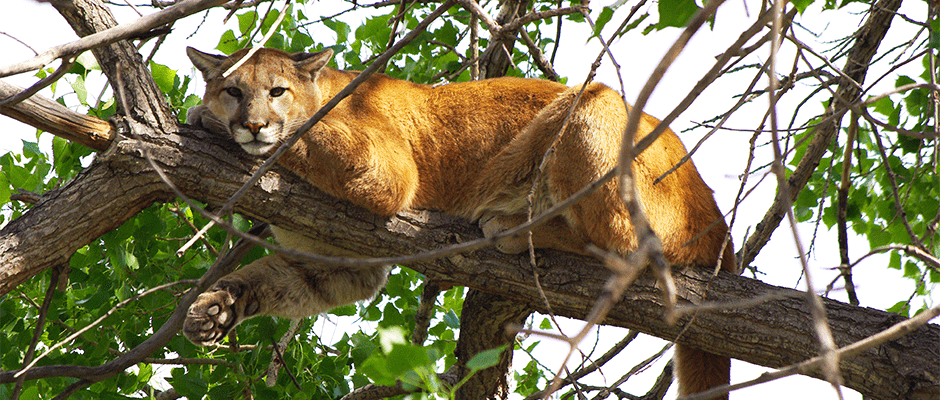

Header Image: A mountain lion lies in a cottonwood tree during the heat of the day. ©USFWS Mountain Prairie