Share this article

Tracking down the plague cycle in prairie dogs

Prairie dogs in the western United States often face outbreaks of plague — an infectious disease caused by the bacteria Yersinia pestis — that can wipe out entire populations of the burrowing rodents in only a month or two, only for them recuperate and repopulate the area again within a few years.

But researchers at Colorado State University wanted to determine where the disease goes in between outbreaks. “If the disease is killing off hosts in a local area, how does it manage to survive?” said Mike Antolin, chair of the Department of Biology at Colorado State University and the principal investigator of the study published in BioScience.

The research team conducted a multi-year study in which they trapped and tested thousands of black-tailed prairie dogs (Cynomys ludovicianus) in the Pawnee National Grassland in Colorado as well the fleas that carry the pathogen that causes plague.

Their analysis showed that the disease doesn’t completely disappear in prairie dog populations, but remains in some individuals within the population. “We’ve done a lot of surveillance and detected plague by collecting fleas and doing molecular analyses months before seeing prairie dogs dying,” Antolin said. “This provides evidence of smoldering transmission before the epidemic begins.”

Antolin said this means it may be possible to make predictions about when another outbreak might occur, especially when climate data is added to the model. “One thing that’s clear about the plague is that it is climate driven,” he said. “In the dry western part of the U.S., it’s rare to have plague outbreaks during drought times and more common during the wet times. It’s like the Goldilocks of pathogenic bacteria.”

And while prairie dogs might be a resilient species, other species that are susceptible to the pathogen are not. “There are implications for black footed ferret conservation,” Antolin said. “They have no plague resistance whatsoever. Controlling plague in prairie dogs where black-footed ferrets are found is critical for black footed ferret conservation.”

Antolin said simply studying outbreaks when they occur isn’t going to help identify when future outbreaks will take place. He hopes this research leads to better ways for predicting the outbreak of infectious diseases in wildlife. “Emergence of pathogens from wild animal reservoirs is the new norm,” Antolin said. “Where the next one comes from, I don’t know.”

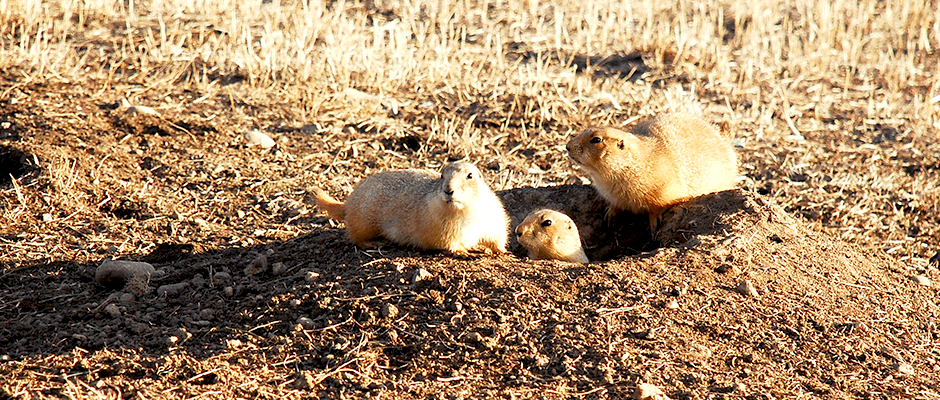

Header Image: Black-tailed prairie dogs in Colorado. ©Dan Salkeld