Share this article

The winter is more bitter for mangy wolves

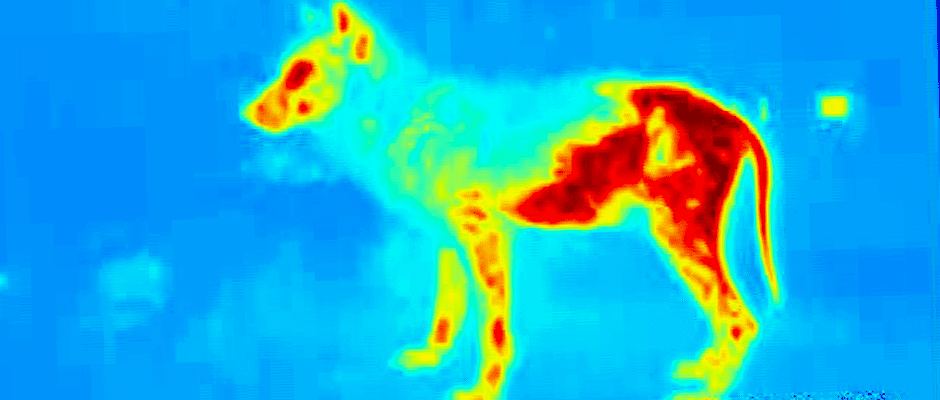

Mangy wolves struggle more to cope with the cold and wind than healthy animals.

“They could either consume more to replace those lost calories through heat or they could move less,” said Paul Cross, a disease ecologist with the U.S. Geological Survey’s Northern Rocky Mountain Science Center in Bozeman, Montana and lead author in a recent study published in Ecology on the way gray wolves (Canis lupus) cope with the mange. “We don’t know whether they’re consuming more but it looks like they’re moving a little bit less.”

Sarcoptic mange is caused by mites that burrow into animals’ skin. It affects one in 10 known wolf packs in the Yellowstone National Park as of 2015.

The researchers used a combination of GPS collars and a combination of camera traps — both regular and using thermal imagery. To assess the mange status of wolves, they also supplemented this data by direct observation. (To read more about the technology, check out The Wildlife Professional’s Spring 2015 article in Field Notes).

They found that mange affected the amount of distance wolves traveled. Healthy animals travel around 10 miles a day on average while mange meant the wolves tended to travel a few miles less on average. Severely infected individuals only moved a few miles every day, and in the worst case, an individual barely moved.

The results also showed that severe infections could increase heat loss at night by around 1240 to 2850 calories per night — around 60-80 percent of an average wolf’s daily energy needs.

While mange can affect an individual wolf a lot when exposed to the elements, Cross said it doesn’t do much damage on a population level.

“When you do the calculations about how many pounds of elk meat [on top of their normal consumption] they would need to consume to mitigate the costs of mange it turns out to be not that many,” Cross said.

This would amount to around 12 additional elk needed for the population of around 40 wolves in the northern Yellowstone area. On average, an individual wolf would need to consume 2-4 pounds more elk meat to survive the winter.

Cross said that their findings show that mange probably doesn’t affect wolves enough to cause a conservation problem in the area, but it’s one of the factors that impact wolf population dynamics. He said that wolves don’t usually die from mange directly, but it’s a factor in deaths.

“It’s predictive of survival rates, but they die due to other causes.”

He also noted that smaller packs seemed to be more affected by individuals infected by mange than larger packs.

“There’s a possibility that there’s a social safety net for infected individuals,” Cross said.

Video credit: USGS

Header Image: A wolf seen through a thermal imaging camera. ©USGS