Share this article

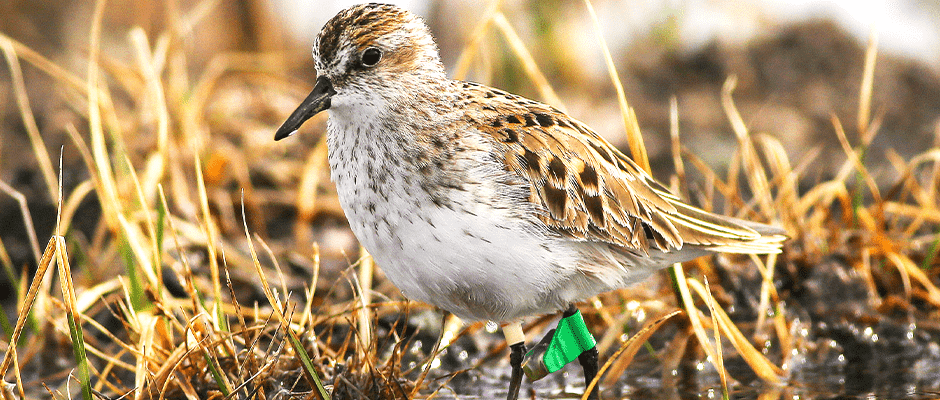

South American sandpiper’s route may explain its decline

Scientists have been tracking the migration of the semipalmated sandpiper (Calidris pusilla) to trace the origins of its population in northeastern South American, which is decreasing dramatically. A new study following the bird confirms that sandpipers wintering on the northeast coast of South America probably hatched in the eastern Arctic. Understanding the risks they face on their migration route, researchers say, may help them understand why the birds are declining.

“Birds declining in eastern South America are much more likely to be from the eastern Arctic,” said Stephen Brown, a TWS member and lead author on the paper published in The Condor. “But they also used the eastern coastline of the U.S., especially in northbound migration.”

From 2011 to 2015, Brown and his collaborators across 18 organizations trekked across eight Arctic research sites, hunted for sandpiper nests and netted and banded the 250 birds they found with light-based geolocators. The biologists returned to the nests the following year to remove the tags and download the light data accumulated over the birds’ migration, which they then translated into daily location estimates.

“That helps us focus on what risks are affecting which parts of the population,” said Brown, director of the Manomet Shorebird Recovery Program. “It tells us where to look for causes of decline and possible conservation actions.”

The eastern population has plummeted by 80 percent in South America and faces multiple threats throughout its migration and lifecycle, he said. As sandpipers, which each weigh no more than two AA batteries, fly north along the eastern seaboard of the United States, they may feel the severe impact of long-term losses in wetland habitat due to development along the coast.

And by quickening summer’s arrival, Brown said, climate change could decrease the amount of food available to chicks in the Arctic.

“Eggs are laid and chicks hatched at a point where there’s a large bloom of productivity in the short arctic summer, and the chicks feed on insects that are super-abundant at that time,” he said. “If the season advances enough that that bloom of insects happens sooner, the chicks hatch at a point where they’ve missed the peak.”

On their way south, the sandpipers may be significantly affected by poaching at coastal stopover sites such as Suriname, Brown said.

Although the findings were mostly in line with what they’d expected, he said, the researchers also observed that some sandpipers from the western population in Alaska migrated to eastern wintering ranges as well. These birds traveled east of the Rocky Mountains and rested along the Gulf Coast before heading to South America.

“It’s a complication factor because it means birds in eastern South America, where the decline is happening, are not all from the eastern Arctic,” Brown said.

Although the results have raised more questions about risks impacting the birds, he said, they’ve ultimately focused the biologists’ research.

“There’s a lot of work to do to understand which particular factors are affecting them,” Brown said. “We know now what geography we should be looking at, and that’s a significant advance.”

Header Image: A semipalmated sandpiper wears a geolocator tracking its migration between the Arctic and South America. ©Brad Winn