Share this article

Researchers explore sika deer’s past to guide its future

Researchers recently looked back about a century ago to determine how sika deer made their way from their native home on Japan’s Yakushima Island to Dorchester County, Md., with the hopes of guiding management of the species, which has been impacting native white-tailed deer, into the future.

In the study published in the journal Biological Invasions, the team reviewed literature and historical records to determine the origin of sika deer (Cervus Nippon) and their journey to Maryland’s Eastern Shore. They also took into account morphological and genetic information of the deer, such as documented bottlenecks in the population, to confirm the origin and path of sika deer from Japan to Maryland.

“It’s important to understand how the deer got from four to five individuals to thousands of individuals,” said TWS member Jacob Bowman, chairman of the Department of Entomology and Wildlife Ecology at the University of Delaware and coauthor of the study. More sika deer now live in Dorchester County than on Yakushima, he said.

After reviewing the literature, the team found that after a brief stopover in the United Kingdom, sika deer showed up in Maryland in the early 1900s when four or five were released on James Island in the Chesapeake Bay. Since then, their population has grown to about 12,000.

Bowman said the deer were able to thrive in the early 1900s in part because they had little competition from native white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) whose population was particularly low at the time due to overexploitation by hunters.

“Sika deer were able to expand without a lot of competition from herbivores,” he said. They became established before white-tailed deer recovered, he said, and their growing numbers blocked the way for white-tails to recolonize in some areas.

“Now, they’re up against each other,” Bowman said.

Although their native habitat lies at higher altitudes , he said, sika deer easily adapted to the tidal marsh in Dorchester County, foraging on both lower-quality vegetation that white-tailed deer can’t consume as well as on the plants that white-tails prefer — a combination that leaves white-tail deer with less to forage on while sika deer consume a wider range of plants.

“White-tails are getting the shorter end of the stick,” Bowman said.

The paper is part of a larger project looking at competitive exclusion between white-tailed deer and sika deer to help guide Maryland Department of Natural Resources management. The agency has recently increased the bag limit for hunting sika deer, but it’s too soon to know the impact on the population so far, Bowman said.

“Maryland wants to keep the population within the current range and not allow them to spread anywhere,” he said. “They don’t want to eradicate it, but hold it where it’s at.”

In the future, Bowman hopes to compare sika calf and white-tail fawn survival studies to see how both are faring.

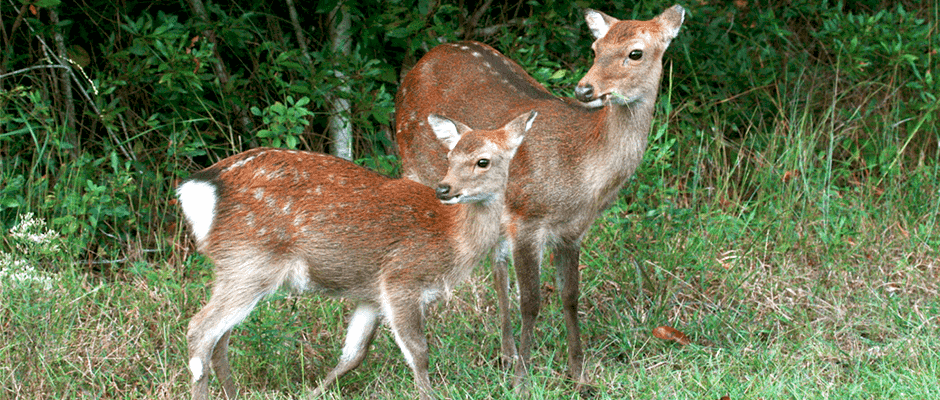

Header Image: Two sika deer forage on Assateague National Seashore in Worcester County, Md. ©Nancy Magnusson