Share this article

No Laughing Matter —

from The Wildlife Professional

Livestock Protection Dogs Conserve Predators, Too

Back in the 50s and 60s, Saturday morning cartoons lit up television screens in many American homes as children, and adults alike, laughed at the antics of animal characters who always survived the cleverly planned attacks and traps set by their adversaries. Warner Brothers’ Looney Tunes cartoons satirized relationships between characters like the rascally rabbit Bugs Bunny and the hapless rabbit hunter Elmer Fudd, and the sly Wile E. Coyote and the lightening-quick Roadrunner.

A lesser known pair of supposed enemies was Ralph E. Wolf and Sam Sheepdog, friendly neighbors whose “work days” started with a routine encounter and exchange of pleasantries at the time clock. After punching the clock and trading collegial morning greetings, Ralph set off on his persistent quest of a lamb chop meal, only to be foiled time after time by Sam’s seemingly lackadaisical efforts to protect his flock of sheep.

Given Sam’s success at deterring wolf depredation, today the offspring of this Berger de Brie sheep dog would be in high demand. Known as livestock protection dogs, this breed and others can reduce — although not completely eliminate — livestock losses to predation. In 2015 alone, predators were responsible for one-third of sheep and lamb losses, with over 194,000 animals killed (NAHMS, USDA 2015).

Man’s best friend has protected livestock around the world for centuries and remains one of the most highly utilized strategies today. In the United States, sheep ranchers also use numerous other strategies to protect livestock from predators, such as fencing, indoor or shed lambing, shepherds, range riders and a host of harassment techniques.

Early Dog Studies

Early in the 1970s, however, only a few U.S. ranchers relied on dogs for guarding livestock. Other than one rancher in Washington State, some Navajo used mongrel dogs to protect sheep. Around this time, studies led by federal researchers within the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research Service set out to identify suitable Old World dog breeds for protecting livestock and determine their effectiveness in reducing predation.

A concurrent study at Hampshire University, which was partially funded by USDA, also looked at livestock protection dogs, while researchers at the Denver Wildlife Research Center (now the National Wildlife Research Center) studied the effectiveness of dogs guarding pastured sheep. These studies, as well as restrictions placed on pesticides available for predator control such as sodium cyanide, resulted in greater interest in using dogs among ranchers, especially sheep producers (Green and Woodruff 1983).

When the formal research concluded in 1986, the federal program now known as Wildlife Services instituted a two-pronged, operational program to educate its own field staff and livestock producers about the potential and management of livestock protection dogs. It also placed 50 to 60 dogs with sheep producers in western states on an experimental basis.

Over the last 30 years, sheep operators have stepped up use of nonlethal methods to protect their flocks, especially livestock protection dogs. In 1994, 28 percent of sheep operations used dogs for protection, with that number growing to 40 percent in 2014. This growth occurred despite some disparity in the success of the early trials in pastures and open ranges. Overall, producers raising sheep in pastures saw greater success compared with ranchers who allowed sheep to graze on open ranges (Green and Woodruff 1988). Nevertheless, the results served as the catalyst for a greater role for dogs in the U.S. sheep industry — one that not only provides livestock protection but also predator conservation.

| USDA Serving Montana Ranchers, FarmersUSDA Under Secretary for Marketing and Regulatory Programs, Edward Avalos, visited a Hutterite community in Rockport Colony near Pendroy, Mont., and blogged about his firsthand look at why Wildlife Services is regarded as an important partner to these communal farming/ ranching operations and their struggles with wildlife damage management. |

An Expanding List of Predators

In the 1980s when researchers were studying the effectiveness of livestock protection dogs, the desire for more robust defense of livestock among sheep operators was driven primarily by the growth of U.S. coyote populations. As recently as 2014, coyotes were still credited with 54 percent of the adult sheep and 64 percent of the lambs lost to predators [NAHMS, USDA]. But today, wolves — and to a lesser degree grizzly bears — are beginning to play a role in overall predator impacts to livestock producers in the northwestern United States.

In fact, while wolves were previously categorized as “other predators” in reports, recent predation levels are significant enough to warrant a separate category. Grizzly bears — which have also become more abundant in targeted recovery areas — have spread to prairies they previously inhabited that are now also supporting sheep flocks. In the state of Montana alone, Wildlife Services depredation investigations due to grizzly predation of sheep doubled in the past year from 44 to 88 between 2014 and 2015.

Enter the Wolf

Since 1975 when protection of wolves began under the Endangered Species Act, recovery efforts have been very successful. But at the same time, wolf predation of livestock has grown. Wildlife Services has cooperated with federal and state wolf management agencies to support wolf recovery but also to lessen the negative impacts. Through depredation investigations, Wildlife Services has provided recommendations for nonlethal, preventive measures and manager-authorized lethal removal in order to increase public tolerance of wolves.

Two areas where these efforts have been in high demand are the Rocky Mountain and Great Lakes regions, where wolf populations have reached and exceeded recovery goals set by wolf managers. In the northern Rocky Mountain region, biologists set the desired recovery level at a minimum of 300 wolves and 30 breeding pairs for three consecutive years. According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, in December 2014, at least 1,657 animals and approximately 85 breeding pairs were counted in the region, with an additional 145 wolves inhabiting areas in Oregon and Washington. These numbers continue to increase, and biologists estimate wolf numbers in the western Great Lakes states of Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan exceed 3,700 animals.

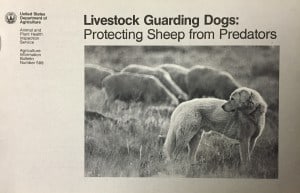

This 1990 USDA publication offered guidance on selecting, training and managing livestock protection dogs as “a full-time member of the flock” that could act independently of people. ©USDA files

Unfortunately, the success of bear and wolf populations results in increased conflicts with livestock producers. Besides the obvious negative impacts of depredation by wolves, bears, coyotes and mountain lions, other indirect effects of these predators such as reduced calf weights in areas experiencing depredation events are also negatively impacting the bottom line for producers. For ranchers experiencing depredation, the costs of weight loss in young animals is becoming potentially greater than the costs of direct depredation losses, pointing to a potentially important and understudied aspect of economic conflict arising from the protection and funding of endangered species recovery programs (Ramler et. al 2014)

The Search for Suitable Dogs

Since the successful reintroduction and spread of wolves throughout the Rocky Mountain region, livestock protection dogs are now being challenged with a larger, more formidable foe. When coyotes were the primary predator, U.S. ranchers relied on readily available Old World dog breeds such as the Great Pyrenees (France), Anatolian shepherd (Turkey), and Akbash (Turkey). These breeds provided good protection and are still in service in certain regions.

However, livestock protection dogs are currently being challenged, outnumbered and ultimately killed by the predators they are intended to stop. The Wildlife Services’ National Wildlife Research Center has taken the lead to evaluate other, more robust Old World breeds that may be more capable and better suited to withstand more formidable conflicts.

Around 2010, American Sheep Industry Association members also began to look at other breeds of

Old World dogs and joined forces with the Wildlife Services’ Predator Research Station in Logan, Utah. Biologists there began contacting ranchers in Europe in hopes of further evaluating their apparent successes with dogs in sheep farming areas that overlap with wolves and bears.

After navigating various hurdles — mostly with the export and import of dog breeds from certain countries — Wildlife Services is again studying the efficacy of several new breeds of dogs. In this current effort, breeds were selected that possess traits that would have a greater chance of surviving encounters with wolves and grizzly bears. Ideally, these dogs need to be aggressive toward predators, tolerant of humans, and athletic enough to thrive in the rugged and remote settings where livestock and large carnivores co-occur.

Livestock protection dogs are socialized early with the animals they will guard so that they will relate to the flock rather than to humans. ©USDA Wildlife Services

Three breeds — Karakachans (Bulgaria), Kangals (Turkey) and Cão de Gado Transmontanos (Portugal) — are part of an ongoing study in the northwestern states of Montana, Wyoming, Idaho, Washington and Oregon. Data collection — including tracking GPS collars on the dogs, wolves and grizzly bears — is focused on determining which, if any, of these breeds are better suited to reduce large predator conflicts with livestock. If the research finds these breeds are more effective in preventing predator attacks as well as losses of livestock, Wildlife Services will identify and develop the most effective training methods along with best management practices to assist producers in using the dogs on their own farms.

Preliminary results from the research look promising. All of the larger dog breeds exhibit high fidelity to their sheep — meaning they stay close to their flocks. Observations show the dogs distinguish between experimental wolf and deer decoys and respond aggressively toward the wolf decoys. Trail cameras and space-use data also confirm that the dogs, sheep, wolves and grizzly bears share the same habitat during the grazing season, but more analysis is needed to determine how often overlap and interactions occur. Fieldwork is slated to wrap up this year and additional data analysis will help to determine whether certain dog breeds are better at deterring grizzlies versus wolves, or whether some are more effective in different environments such as forested, open or fenced landscapes.

Protecting the Protectors

Given its mission to provide federal leadership and expertise to resolve wildlife conflicts in a manner that allows people and wildlife to coexist, Wildlife Services is committed to helping producers reduce depredations and, whenever possible, in a non-lethal manner.

While Wildlife Services has taken the lead to identify more effective breeds to circumvent wolf and grizzly bear confrontations with livestock, it also has undertaken an effort to reduce potentially threatening confrontations between livestock protection dogs and humans. More people are using public lands for a variety of purposes including hiking, biking, horseback riding and other recreational activities, and some of these areas are also used for livestock grazing.

Unfortunately, conflicts with humans and the dogs have occurred. Mountain bikers have triggered protective behaviors by some dogs and a few of these interactions have resulted in injury to humans. Additionally, increasing urbanization has led to conflicts between livestock protection dogs and residents in historically rural areas. As a result, land managers are considering the need to keep sheep farther from new recreational trails, and some ranchers are proactively exposing dogs in training to bikes.

Larger breeds of dogs are needed to protect sheep from attacks by wolves and bears. This Great Pyrenees dog lives with and guards a Montana sheep flock from predators year round. ©Jack McRae

In collaboration with the U.S. Forest Service, the Bureau of Land Management, and the American Sheep Industry Association, Wildlife Services created informative signs and brochures about livestock protection dogs and is disseminating the materials in areas where the dogs and public may intersect. Trailheads, visitor centers and highway fences are just a few of the places where people may encounter these informational resources, which provide suggestions for appropriate behaviors around the dogs and the flocks they protect and also explain the purpose and need for livestock protection dogs.

Rising up to the Challenge

With the surge in the public’s empathy for all animals, the field of wildlife damage management is undergoing a period of tremendous change. In order to be successful, those involved — including Wildlife Services — must consider a wide range of public interests that can conflict with one another: wildlife conservation, biological diversity and the welfare of wild and domestic animals, as well as the use of wildlife for enjoyment, recreation and livelihood. In living compatibly with wildlife today, multiple strategies to reduce conflicts are often necessary.

Livestock protection dogs may very well become a key means of protecting livestock while at the same time conserving expanding wolf and grizzly bear populations (Gehring and VerCauteren 2013).

No doubt, Sam and Ralph would probably agree.

|

Michael Marlow, CWB®, Mag, is a resource management specialist for USDA Wildlife Services based in Ft. Collins, Colo. |

Header Image: Ben Hofer of the Hutterite Rockport Colony near Pendroy, Mont., interacts with a Kangal dog placed by researchers at the National Wildlife Research Center who are studying the potential use of these livestock guard animals in areas with large predators such as wolves and grizzly bears. The Kangal breed is gentle and trustworthy with their people and animals, but if the need arises, they can become fiercely protective. ©Edward Avalos