Share this article

Model predicts wild pig distribution in Saskatchewan

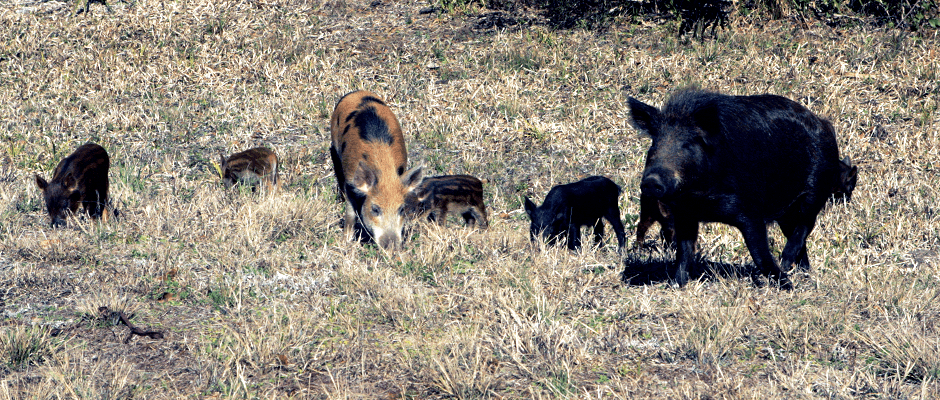

There are some preconceived notions that free-ranging wild pigs (Sus scrofa), an invasive species in North America, are unlikely to survive in cold areas since many of them are invading warm states, such as Texas and California. In fact, most modelling efforts in the United States use climatic limitations as a factor in predicting wild pig distribution and spread.

However, new research published in the journal Landscape and Urban Planning shows that wild pigs are expanding in Saskatchewan, Canada, where the average annual temperature is around 2.5 degrees Celsius (37 degrees Fahrenheit).

“There’s an assumption that they would never survive in Saskatchewan,” said study author Ryan Brook, an associate professor in the College of Agriculture and Bioresources at the University of Saskatchewan who is also a TWS member. “But they were very much adapted to do so. They live in Siberia. Why wouldn’t they survive Canadian winters just fine?” Brook continued. He said that the pig’s thick hair and penchant for making what he refers to as “pigloos” beneath the snow help them survive the cold.

With climate not serving as a strong predictor of wild pig occupation in this situation, the researchers in the study turned to the propagule pressure hypothesis, which suggests that the size and frequency of introduction events best predicts establishment success of invasive species.

In the study, Brook and his colleagues used previous data from camera traps collected about five years ago that showed evidence of pigs reproducing in the wild. “They were producing two litters a year of about four to six piglets per litter,” he said. In conjunction with this data, Brook also sent out surveys to rural municipalities in Saskatchewan where people could report their sightings of wild pigs. After mapping out 296 municipalities, they found that nearly 50 percent of them had seen wild pigs at least occasionally. “That’s much higher than anybody expected,” he said.

The researchers then looked at the national trends for domestic wild boar production in Saskatchewan, which showed a peak of 18,000 pigs in 1996 before dropping down to about 3,000 in 2011 when the market began to fail. Comparing these trends with survey data, the team determined that the best predictors of pig distribution included proximity to domestic wild boar farms and habitat type — the wild pigs in the study showed preference for areas with lots of farmland and fewer roads or highways.

Through incorporating domestic wild boar farm distribution and capacity information into existing habitat-based models, the researchers were able to improve the predictive abilities of those models. Brook hopes the predictive maps that he and his colleagues created will help managers in Saskatchewan determine how and where to apply their limited resources to better control the spread of wild pigs. Furthermore, if a wild pig is spotted, the predictive maps can also help determine the pig’s range size and where managers should focus their eradication efforts.

Brook said there are currently eradication efforts in the field, but simply killing off a bunch of pigs might actually result in the population increasing since the pigs that were missed might spread out and establish more populations.

“There’s an emphasis on removal, but not an understanding of the problem,” he said. “You can’t identify ways to improve the program unless you have really good science to back it up. That’s the role we’re playing.”

One of Brook’s suggestions is enforcing guidelines to keep wild boars inside fences and tagging them in case they do escape.

The next big step, he said, is collaborating with the U.S. government to build a similar North American scale model. The U.S. currently has a model to predict distribution of feral pigs but it’s mostly based on climate data, which Brook said seems to not be as big of a factor as originally thought.

“The pigs are also found in the Peace River of Alberta,” he said. “It’s much, much farther north than anybody thought they would be. We need to reevaluate what we think is going to happen.”