Share this article

JWM study: Non-perching birds avoid gas wells

Grassland songbirds have suffered more declines than any other group of birds in North America because swaths of their habitat have been degraded by agriculture and development, including natural gas infrastructure. Ongoing research from Alberta suggests that birds that don’t perch avoid gas wellheads, whereas perching species are more likely to be found around these tubes erected on the prairie.

“Birds that like fences and shrubs to perch on, whether it’s to vocally display for breeding, look for predators or get to food sources, seem to like to be near gas wells,” said Jennifer Rodgers, first author on the paper published in the April issue of the Journal of Wildlife Management.

Rodgers began examining the impact of conventional shallow gas wells on grassland songbirds for her master’s work, part of a longer term study development at the University of Manitoba on how these birds respond to continuing oil and gas development. She wanted to see how the four-meter-tall orange tubes influenced how many birds were nearby. New wellheads promote the growth of invasive species, so she was curious about how changes in vegetation or numbers of wells might affect birds.

In 2010 and 2011, Rodgers and her fellow researchers recorded all the birds they observed and heard in 10 minute periods at natural gas sites in southeastern Alberta. They analyzed the data for the nine species that they found most often on their plots: the Baird’s sparrow (Ammodramus bairdii), brown-headed cowbird (Molothrus ater), chestnut-collared longspur (Calcarius ornatus), clay-colored sparrow (Spizella pallida), horned lark (Eremophila alpestris), Savannah sparrow (Passerculus sandwichensis), western meadowlark (Sturnella neglecta), Sprague’s pipit (Anthus spragueii) and vesper sparrow (Pooecetes gramineus). The biologists also examined plant density and height in these regions. Then they used modeling to figure out how the infrastructure and vegetation influenced the species’ abundance.

The researchers found that “birds that don’t like differences in vegetation height, prefer shorter vegetation and don’t perch didn’t like the infrastructure,” Rodgers said.

Though the researchers noted changes in vegetation near gas wells and roads, this did not explain the birds’ responses in the study, she said. This finding deviated from previous research from elsewhere in the country, which drew a connection between altered vegetation around wellheads and birds’ responses.

Still, “some bird species can be sensitive to the crested wheatgrass (Agropyron cristatum) that proliferates around the tubes and chokes out native grasses,” Rodgers said.

“Making sure oil and gas companies are reseeding with native seed mixes is going to be important,” she said. “To reduce impacts to non-perching species such as the at-risk Sprague’s pipit, we suggest drilling techniques that minimize the amount of surface infrastructure installed.”

TWS members can log into the member portal to read this paper in the April issue of The Journal of Wildlife Management. Go to Publications and then The Journal of Wildlife Management.

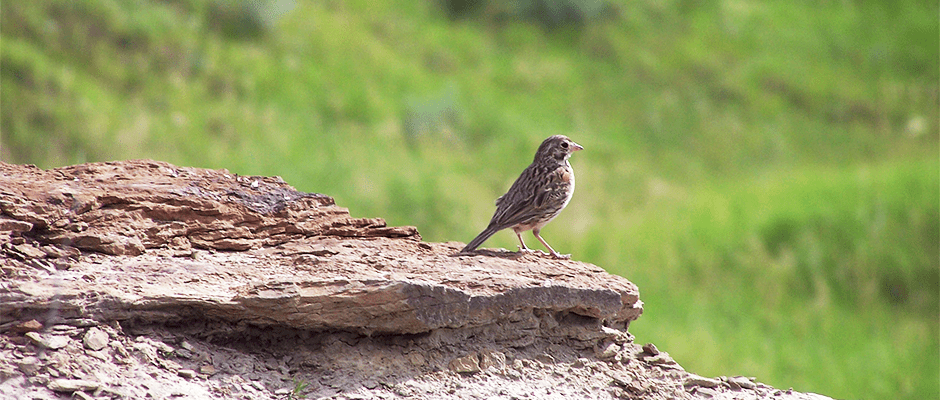

Header Image:

A vesper sparrow, a perching grassland songbird, rests near shallow gas wells in southeastern Alberta.

©Lionel Leston