Share this article

JWM study: Fire, nest locations affect gopher tortoise predation

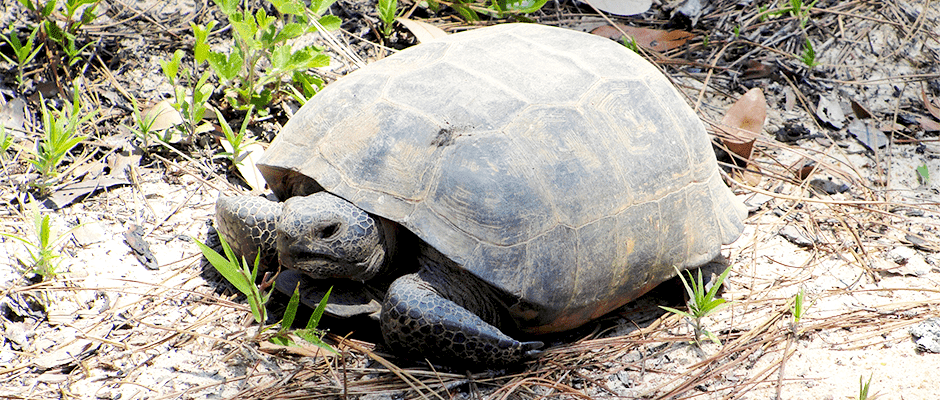

Gopher tortoises (Gopherus polyphemus), which live in the longleaf pine ecosystem, are declining throughout their range due to not only habitat loss and fragmentation but also potentially high nest predation rates.

The tortoises are listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act west of Mobile and Tombigbee rivers in Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana. In the eastern portion of their range, where a recently published study took place, gopher tortoises are considered a candidate species for federal listing.

An active gopher tortoise burrow. The bare sand in front of the burrow entrance is called the apron. ©Michelina Dziadzio

As part of the study published in the Journal of Wildlife Management, a research team led by Michelina Dziadzio while at the University of Georgia, looked at different environmental factors that might influence nest predation for the species. Dziadzio, a member of The Wildlife Society, is currently the gopher tortoise GIS and monitoring coordinator with the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission.

Gopher tortoises usually nest in their burrow’s apron — the loose sand at the entrance of the burrow. However, tortoises also sometimes use open sandy sites not near burrows, and are very good at covering up their tracks, making it hard for researchers to find their nests.

In the study, Dziadzio and her colleagues created artificial nests using chicken eggs that resembled tortoises’ natural nests in order to compare difference in predation between the two kinds of nests. Because they found minimal differences in terms of predation, Dziadzi inferred that she could use the artificial nests to study the effects of environmental factors on predation.

They placed the artificial nests in different areas including active burrow aprons, inactive burrow aprons and open sandy sites away from burrows. Dziadzio and her colleagues monitored the tortoise nests for close to two months to determine if the nests were disturbed or the eggs were removed. At some of the nest sites, the researchers put up trail cameras to capture which predators were depredating the nests. The most common predator observed was the nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus) which is nonnative, but raccoons, opossums and coyotes were also recorded on videos.

After reviewing their data and using models that included the effect of a number of environmental factors on predation rates, the team found that artificial nests in open areas away from the burrow aprons had a much higher nest success rate. “Because burrow aprons had higher predation rates, this suggests predators may be cueing in on burrow aprons as a source of food,” she said.

The researchers’ models also showed that burn year played a role in nest success. “Fire is essential to the maintenance of the longleaf pine ecosystem,” Dziadzio said, adding that land managers typically burn on a two to five-year interval.

The team found that if there was a burn two to five months before the nests were deposited, those nests had a higher risk of predation than in the sites that were not burned that year.

Dziadzio says these findings mean there are potential tradeoffs when using prescribed fire to maintain habitat for species including the tortoise, and understanding that fire also increases nest predation in the year of a burn. “You have to weigh the benefits and costs of your prescribed fire interval,” she said. Dziadzio suggests considering prescribed fire intervals of two to three years with alternating burn cycles. This should allow managers to maintain the structure of the ecosystem, provide suitable nesting habitat away from burrows, and also allow for years with no fire and potentially higher nest success.

In some areas managers exclude or remove predators including raccoons, armadillos and coyotes from the ecosystem to reduce the threat of predation, but according to Dziadzio, “it’s not necessarily practical or cost effective in a lot of situations.”

“Our research suggests that we may be able to adjust our management practices to potentially increase nest success, an approach that might be more cost efficient than predator exclusion. However, future research should evaluate whether nest site selection is dependent upon availability of suitable nesting habitat away from burrow aprons” she said.

Header Image: An adult gopher tortoise. Gopher tortoises face habitat fragmentation, habitat loss and potentially high nest predation rates. ©Michelina Dziadzio