Share this article

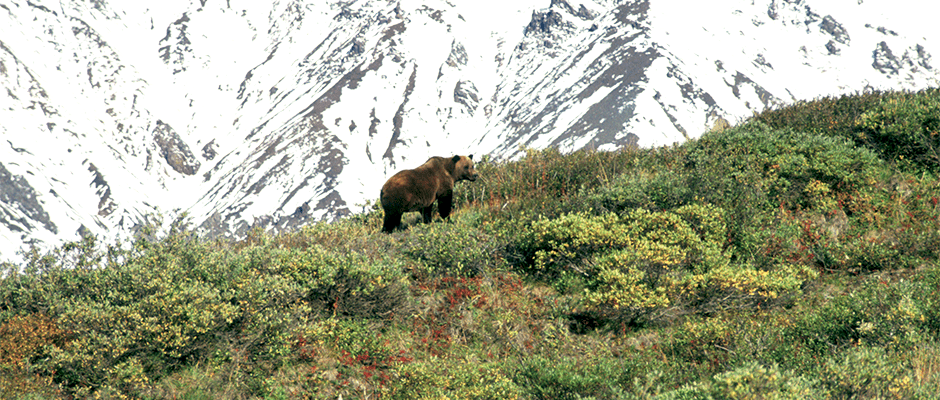

JWM: Denali grizzlies self-regulate their population

In the 1990s, researchers at Alaska’s Denali National Park began noticing something strange. Many of the adult female grizzly bears (Ursus arctos) emerging from dens in the springtime on the caribou calving grounds seemed to be unusually skinny. They also noticed that most of the newborn cubs disappeared each summer.

Biologists took blood samples to determine if the cause was disease. It wasn’t. Could the bears’ body conditions, they wondered, be affecting cub survival?

In a study recently published in The Journal of Wildlife Management, the researchers looked back at these data to see if it could help with other grizzly populations near carrying capacity today.

Beginning in 1994, the team measured body fat of grizzlies before they entered their dens in September and when they emerged in May. They also kept track of births and deaths, and they estimated density. After comparing the bears’ vital rates with a nearby hunted population, they determined the state of the bears in the park and found they were regulating their population in the face of limited food resources.

“What we found is that if a female doesn’t put on enough body fat in the fall, she has a high probability of losing all or most of her litter the next year,” said Jeff Keay, lead author of the study, who is now retired from his research scientist position with the U.S. Geological Survey. “Female body condition pre-denning was significantly correlated with cub survival the next year. Yet birth rates remained very high.”

Keay and his colleagues determined there were 37 bears per 1,000 square kilometers, the survival of adult and subadult bears of both sexes was high, yet the population appeared to be declining slightly during the years of study. With male bears controlling access to the primary protein sources, and yearly variation in berry availability, female bears struggled to put on enough body fat and had fewer surviving cubs, Keay said. “Cubs deaths appeared to regulate the population size.”

The high birth rate coupled with high cub and yearling deaths indicated the population was naturally regulated, with no humans hunting the Denali grizzlies. Keay said. “And it appears bears regulate themselves by managing the number of bears that make it into adulthood.”

The research was conducted decades ago, but the biologists believe it has implications for current bear populations, including the Yellowstone population, which may be nearing carrying capacity. Keay suggests the high mortality of cubs observed in Denali means monitoring cub survival should be done over many years in order to understand populations near carrying capacity. “Further research is needed to understand the balance between predation and nutrition in grizzly bear population regulation,” he said.

TWS members can log into Your Membership to read this paper in the Journal of Wildlife Management. Go to Publications and then Journal of Wildlife Management.