Share this article

How Hawaii’s invasives influence the nutrient cycle

Invasive species on Hawaii Island — also known as the Big Island of Hawaii — likely become a nutrient resource for other invasive scavengers after they die, which researchers say will perpetuate the presence of invasives in the already threatened ecosystem.

In a study published in the journal Ecosphere, a team of researchers from the University of Georgia’s Savannah River Ecology Laboratory studied scavenging of vertebrates and invertebrates of invasive species on the island by using camera traps and radio transmitters.

“We wanted to see what was eating the invasive species that have significant populations on the island,” said Erin Abernethy, a PhD student at Oregon State University and the lead author of the study in a press release. “And, we wanted to identify the percentages of carcasses eaten by invasive vertebrates and invertebrates.” This study is especially important for management of invasive species in Hawaii, where there are the highest number of endangered and threatened species in the United States.

As part of the study, the researchers set up 647 individual carcasses of invasive amphibians, reptiles, small mammals and birds along with camera traps on three different landscapes within the Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park and Pu’u Maka’ala Natural Area Reserve. The team also placed radio transmitters on 17 of the carcasses in order to determine if they were consumed after being removed from the camera trap site.

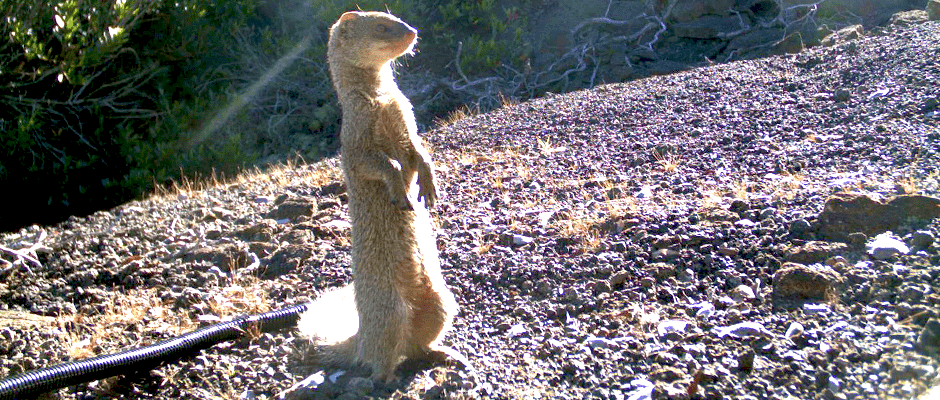

The camera traps showed invasive vertebrates, including the mongoose (Herpestes javanicus Geoffroy) and rats removed 55 percent of the carcasses. While this number was 10 percent more than invertebrates such as yellow jackets and fly larvae, the team was surprised by the lack of discrimination in what the vertebrates ate.

“We anticipated that vertebrates would quickly find and remove large carcasses, but we discovered that the vertebrates were skilled at acquiring all types of carcasses,” Abernethy said. “They were adept and highly efficient at finding the smallest of resources.” Abernethy says these small resources include coqui frogs (Eleutherodactylus coqui), a small frog that’s native to Puerto Rico, as well as small geckos. They consumed these small, but important prey species before other native species got the chance to scout them out.

The researchers say this information shows a “positive feedback loop,” which means the more invasive species live on an island, reproduce and die, the more nutrient resources they leave for other invasive species that feed off of them. As a result, the ecosystem is invaded further.

This is especially problematic for native species such as owls and hawks, which weren’t detected at all during the study, says Abernethy. “It is essential to know were nutrient resources flow in a highly invaded ecosystem,” said Olin Rhodes Jr., a wildlife ecologist and coauthor of the study.

Header Image: A mongoose basks in the sunlight in Hawaii Volcanoes National Park. ©Erin Abernethy