Share this article

High school project gives turtles a head start

When Brian Bastarache heard about efforts at Assabet River National Wildlife Refuge to recover threatened turtles, he saw an opportunity to give both the turtles and his students a head start.

The director of the Natural Resource Management Program at Bristol County Agricultural High School in Dighton, Massachusetts, Bastarache teaches courses in wildlife biology, fisheries and outdoor skills. During summers, he works as a biologist for an environmental consulting firm involved with restoring Blanding’s turtles (Emydoidea blandingii), one of several Northeast turtle species that have dramatically declined.

Brian Bastarache cradles a trio of hatchling turtles at Bristol County Agricultural High School’s rearing facility. ©John A. Litvaitis

At Assabet, biologists were taking turtle hatchlings from a nesting site to stock a vacant habitat. But Bastarache knew that could be a problem. Typically, only about a quarter of the tiny hatchlings — which weigh just 10 grams when they emerge from their eggs — survive. They’re vulnerable to predation by chipmunks (Tamias striatus) and raccoons (Procyon lotor) in the uplands and bullfrogs (Lithobates catesbeianus) and herons (Ardeidae) in wetlands. But as they grow, their mortality rates drop.

If the hatchlings could get a head start before entering the wild, Bastarache knew, this new population might stand a better chance.

Head starting has been done for decades. The programs involve keeping hatchlings in captivity until they’re large enough to be relatively secure from predation. It’s usually done to increase an existing population, not establish a new population though, and its success

with turtles has been mixed. Since Blanding’s turtles don’t reach sexual maturity until they are 14- to 20-years old, establishing a new population by stocking juveniles can take a lot of time and money.

But Bastarache saw it could also be a chance to help his students and the hatchlings.

Bastarache converted a greenhouse at the Bristol school into an impressive rearing facility with an array of water-filled containers with pumps and filters and artificial plants meant to resemble wild habitat.

Hatchlings brought to the greenhouse are provided with summer-like conditions and ample food for the first nine months of life, September to May. Instead of hibernating during their first winter, they remain active and grow. Overwinter survivorship is more than 95 percent — substantially better than wild-raised hatchlings. After nine months, most grow to a size equivalent to a 3- or 4-year-old wild turtle.

Bastarache’s students take on the care of the young turtles using approved biosecurity protocols. Their routine includes monitoring conditions of the rearing trays and tanks, evaluating each hatchling’s growth and development and providing weekly measurements to research partners. Turtles that seem to be underperforming are taken aside and given special attention, including extra rations to increase weight. The students are also expected to become experts on the biology of their turtles and share their knowledge with visitors who attend regular events at the rearing facility.

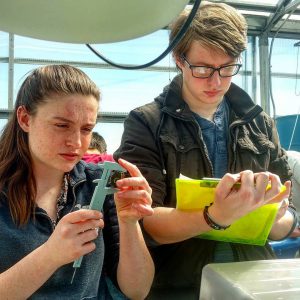

High school students record the length and weight of hatchling turtles they plan to release into the wild. ©Brian A. Bastarache

Their work is complemented by biologists from the Savannah River Ecology Lab at the University of Georgia led by Kurt Buhlmann, who has been involved in turtle conservation projects throughout the world. At first, they feared the captive-raised hatchlings would be “less wild” and have difficulty once released, but their monitoring revealed that turtles from the head-start program are adapting well to home in the wild.

In May, when the head-started hatchlings are ready to be released, students and collaborators travel to the Assabet refuge and distribute them. Since 2009, 674 juvenile Blanding’s turtles have gone through the head-start program and been released at the refuge.

Since starting the program, Bristol students have expanded their head-starting efforts to include 12 species, including northern red-bellied cooters (Pseudemys ubriventris) for releases in nearby Plymouth County and wood turtles (Glyptemys insculpta) for release the Great Swamp National Wildlife Refuge in New Jersey.

Given the life histories of the turtles involved in the head-start program, it may be too soon to evaluate the success of the stocking efforts. But for many of the students involved, their work recovering at-risk turtle populations may be a head start in an exciting career in conservation.

TWS member John Litvaitis, PhD, is a consulting biologist and emeritus professor of wildlife ecology at the University of New Hampshire.

Header Image: Blanding’s turtles face a delicate early life, but giving them a head start indoors can improve their survival in the wild. ©Kurt A. Buhlmann