Share this article

Fieldnotes: Acoustic Recorders Track Bird Activity

Recording devices present new opportunities for researchers to monitor bird populations, according to recently published studies.

In California, researchers are using passive acoustics devices to listen in on elusive marbled murrelets (Brachyramphus marmoratus) that nest high up in some of the world’s tallest trees.

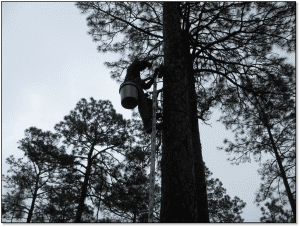

Marbled murrelets nest high up in redwood trees such as these in Headwaters Forest Reserve near Eureka, Calif. ©Bureau of Land Management, licensed by cc 2.0

“We’re listening to the sounds of the birds flying back from the ocean or flying to the ocean from their nest sites in the forest,” said Abraham Borker, a PhD student in ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of California-Santa Cruz and the lead author of a study published in the December issue of the Wildlife Society Bulletin.

The birds make a sound similar to gulls, potentially to alert their chicks or mates incubating nests. In the past, researchers on the ground would sit near at certain sites and count the amounts of murrelet sounds they heard as a way to figure out how many birds live in a given area. But monitoring these sites has traditionally cost a lot of money because it involves having multiple boots on the ground listening for the murrelet calls.

Borker said that researchers had great success in attaching passive acoustic recorders 10-15 feet up on redwood trees to capture murrelet calls. While they didn’t detect as many murrelet calls per morning during established monitoring times set by the U.S. Forest Service, the devices could capture more murrelets over the season as they sampled 10 times as many mornings.

The devices were also combined with recognition software that could accurately distinguish murrelet calls from the rest of the noise picked up by the recorders and flag them for researchers. It wasn’t perfect —from 20,000 calls, only 7,000 were from murrelets. Of those, they identified 2,400 individual birds by analyzing the spectrograms.

“The acoustic tools could measure the presence of murrelets very accurately,” Borker said.

The acoustic tools shouldn’t completely replace monitoring, Borker said, as humans can use their eyes to spot possibly silent birds. But using the devices could increase the overall scale of murrelet monitoring at a much lower cost.

“This gives us a tool to evaluate management actions in those breeding habitats that they occupy. And it increases the scale in which we can do that,” he said.

A Wild Turkey Chase

Researchers have also used autonomous recording units to track gobbling levels among male wild turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo spp.) in Georgia in another recent study published in the same issue of the Wildlife Society Bulletin.

“There was this perceived decline in turkey populations throughout the Southeast according to a number of different wildlife agencies,” said Derek Colbert, an associate wildlife biologist with APHIS and the lead author of the study.

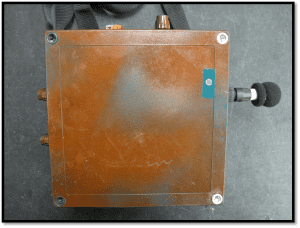

Colbert, a member of The Wildlife Society, and his coauthors collected data in 2011 and 2012 at two sites in Southwest Georgia as part of a larger project to track the birds in the state. He and his coauthors put seven devices at two different sites — one where turkeys continued to be hunted and one where they hadn’t been hunted since the 1980s.

The devices recorded 30–40 percent more gobbling at the site where the birds are not hunted. In the other area, hunters are only allowed to harvest males, and the studies showed that most females had already started nesting by the time the hunting season started.

“The structure of their current hunting season seems to be working out pretty well,” he said.

As far as the devices are concerned, Colbert said that the gobbling data they gathered was extremely successful. They recorded 7,000 gobbles from the various recorders over the two years of the study. But the 20,000 hours of recorded data was difficult to process, and they ran into problems developing software that would automatically identify gobbles from other noise.

“One of our biggest take aways was the amount of data we were able to collect just using one person,” Colbert said. Developing the software further to automatically identify gobbles would help them even more in the future. “If we can get those two aspects on the same page … you’re talking about the ability for one person to make some large conclusions based on a large amount of data and a fairly short amount of time.”

Header Image: Marbled murrelet in flight. ©Aaron Barna, licensed by cc 2.0