Share this article

Connecting wildlife in the face of climate change

While past research has shown that habitat corridors help provide refuge for species across roadways and other urban or disturbed areas, new research shows the wildlife corridors might also help soften the blow from climate change.

“Corridors connect two patches of forest,” said Jenny McGuire, a research scientist at Georgia Tech and lead author of a recent study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. While fragmentation can block the ability of animals to move across the landscape, McGuire notes that strategically placed habitat corridors such as overpasses and underpasses could help facilitate the type of movement that plants and animals need in order to adapt to climate change.

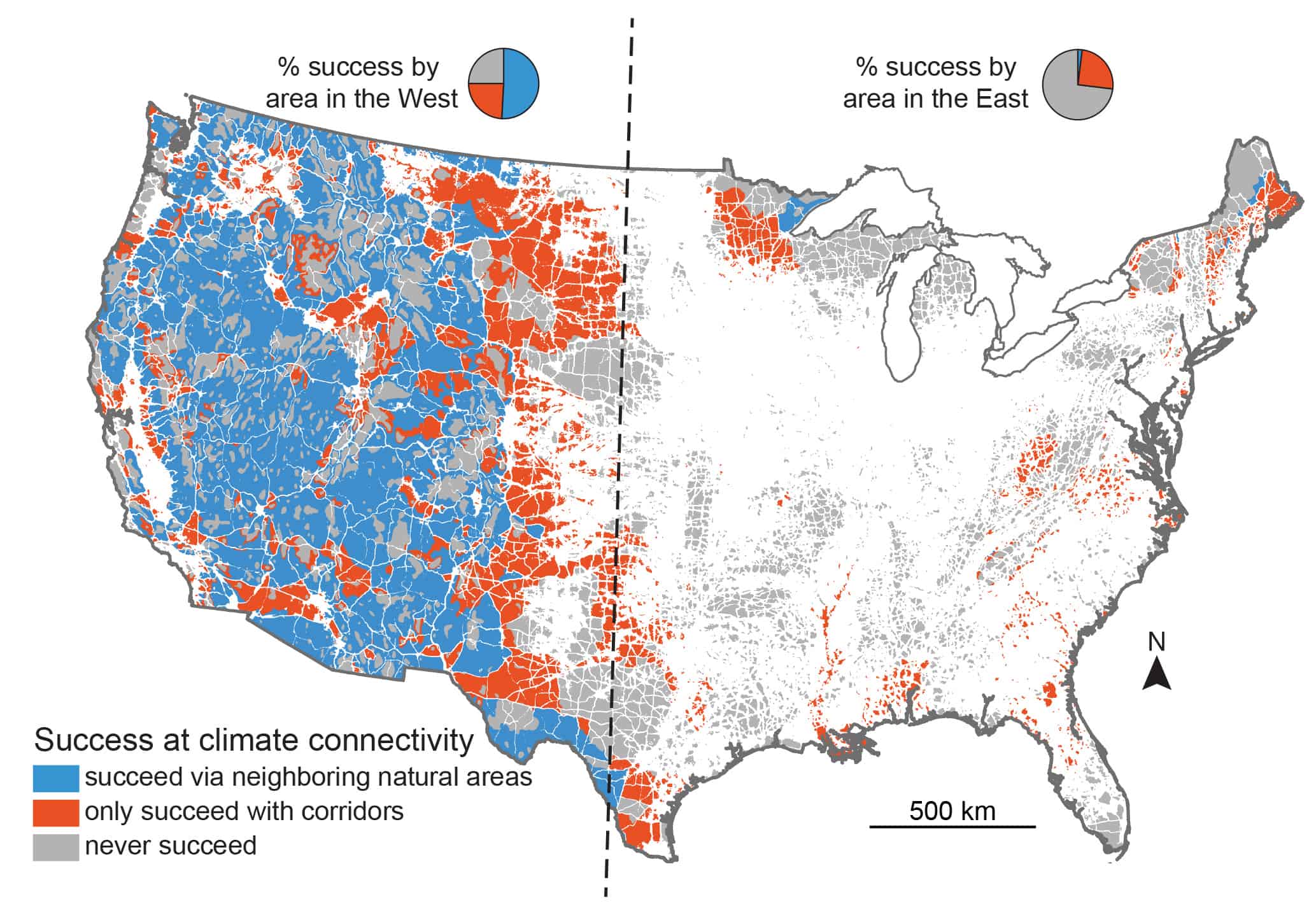

This map shows the regions of the U.S. where plants and animals could potentially evade predicted climate change. Blue areas show where they will be able to adapt to climate impacts given current conditions, orange areas are where they will be able to succeed only if they are able to cross over human disturbed areas, and grey areas are areas where they cannot succeed by following climate gradients. ©Jenny McGuire, Georgia Tech

As part of the study, McGuire and her team looked at the most strategic areas to place habitat corridors to help wildlife deal with warming climates. The researchers identified natural or undisturbed patches of land in the United States as well as developed areas with houses, roads and agricultural fields. They created a “human impact” map based on that information and used it to determine how to connect natural habitats in the presence of these developed areas.

After reviewing the map, the researchers found that, compared to the eastern U.S., western areas have greater temperature ranges and more natural areas allowing wildlife species in these areas to move to environments better suited to them in the presence of climate change. For example, the western part of the country has plenty of temperature variation thanks to its high, steep and cold Rocky and Sierra Nevada Mountains, which already serve as refuge for wolves, grizzly bears (Ursus arctos) and other wildlife.

However, McGuire and her team found that only 2 percent of the eastern U.S. has the connectivity that species such as salamanders or frogs in eastern Florida and Georgia would need in order to migrate as a result of climate change. “In the eastern U.S., natural areas are much more fragmented because of increased and higher human densities,” McGuire said. Here, there’s also a lower temperature gradient, according to McGuire. As a result, she says if species need to search for cooler temperatures, they might have to travel quite far, putting them in danger of road collisions and other factors of urban development. McGuire and her team also found that the coastal plains in the Southeast were important to connect to more inland areas.

Although the study didn’t focus on specific wildlife species, according to McGuire, it helps provide a bigger picture for the types of areas in which wildlife might benefit from corridors. “Some areas are influenced more by climate change than others,” she said. “It’s good for a broader planning basis.”

Header Image: Jenny McGuire is interested in spatial questions about the ecological and evolutionary implications of climate change. In a new study, she and her co-authors look at climate connectivity in the U.S. ©Rob Felt, Georgia Tech