Share this article

Climate change threatens parasites with extinction

Next to polar bears clinging to melting icebergs drifting through the sea, slimy, coiled worms floating in jars of formaldehyde might not make much of a case for conservation. But a global team of biologists recently found that parasite species worldwide are threatened by climate change, and their extinction could upset ecological and human health.

“Parasites are affected by climate change just like any other group,” said Colin Carlson, first author on the study published in Science Advances.

In 2015, researchers around the world began georeferencing museum parasite specimens and compiling what’s now the largest parasite database to remedy the paucity of information about this group of animals. They mapped the distributions of about 500 species, projected how their ranges would shift with climate change and calculated their extinction risk given the habitat loss they’d experience.

“Parasites are threatened not just by climate change but also by the loss of their hosts based on climate change,” said Carlson, a doctoral candidate at the University of California, Berkeley. “When you account for this compound vulnerability, that pushes parasite extinction rates to about one in three species.”

Fleas and ticks are especially at risk on a global scale, he said, and most worms, except spiny-headed worms, are endangered as well.

“Parasites going extinct is bad news for ecosystems,” Carlson said. “We think of parasites as a bad thing, but they play a lot of incredibly important roles in the ecosystem.”

Like predators, Carlson said, they keep populations in check. Parasites can compose most of an ecosystem’s biomass and travel through 80 percent of the food web, he said. These animals also have specific adaptations that drive other species’ survival from behind the scenes, he said.

Horsehair worms in Japan, Carlson said, are cricket parasites whose ultimate host is an endangered trout. They alter the crickets’ behavior to guide them into streams, supplying 90 percent of the fish’s diet, he said.

“There are 300,000 species of parasitic worms alone,” Carlson said. “We know little about what parasites are doing, but based on examples we have, they’re irreplaceable for nature.”

The extinction of certain parasites could even facilitate invasions by more harmful ones in new environments, he said, with enormous consequences for wildlife and people.

“Climate change is a lottery,” Carlson said. “Everything is being reshuffled. Some things are invading new places, and some are going extinct. All that fits into one big pattern that is not great for ecosystems and humans.”

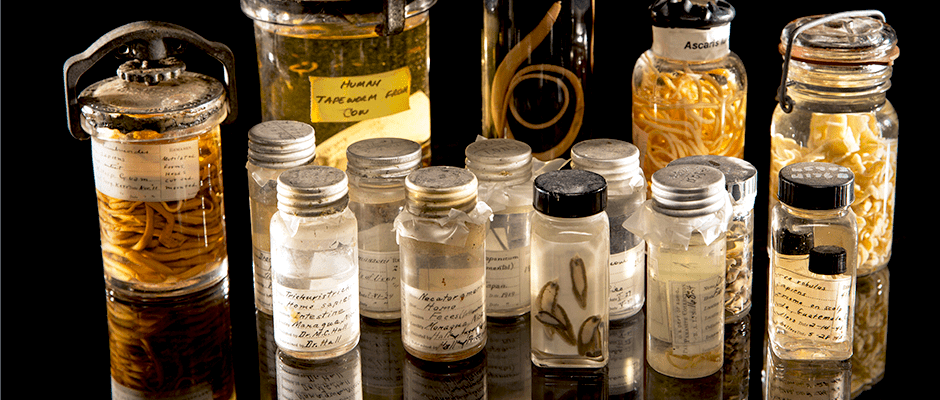

Header Image: Specimens from the Smithsonian's National Parasite Collection sit in jars at the National Museum of Natural History. ©Paul Fetters