Share this article

Citizen Scientists Track Declining Box Turtles

The bowl-sized reptiles could be living in your garden or you may have helped them cross the highway. You may have caught them, or kept one as a pet when you were a kid.

Now, wildlife conservationists worried that eastern box turtles (Terrapene carolina carolina) may be disappearing from North Carolina have combined a long-term citizen science tracking program with GPS tracking data to try to better understand the population status of the reptiles.

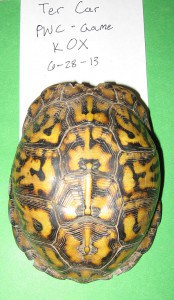

This uniquely patterned shell is marked with letter codes that enable researchers at the Piedmont Wildlife Center to identify each turtle.

“We believe they’re in decline but we don’t have the data to back that up,” said Sara Steffen, the conservation coordinator of the Piedmont Wildlife Center (PWC) in North Carolina.

In North Carolina it’s currently legal to take up to five reptiles out of the wild at any one time, as long as the species isn’t listed as endangered, threatened or of concern.

Box turtles currently have no protection under any of those categories in the state, and Steffen believes that the pet industry, habitat fragmentation and people catching and eating the turtles are all contributing to declines. If they can prove this, the reptiles could receive government protection.

“If the law is out there hopefully we’ll have less people taking them as pets,” she said.

PWC is trying to change this lack of status by gathering as much long-term data as it can on the turtles in North Carolina through a long-term citizen science project called Turtle Connection that gathers photos and range information from interested people across the state, with a particular focus on the triangle area between Durham, Raleigh and Chapel Hill.

Each box turtle has a distinctive pattern that sets it apart from the others much like human fingerprints, according to Steffen. As part of the tracking effort, people take photos of turtles they find in their areas, both of the top and of the bottom of their shells, and send them to the PWC. The program has received 180 entries since starting in 2012, and the PWC is currently working on developing software that will automatically recognize duplicate turtles.

Common threats the turtles face include people taking them out of the wild as pets or displacing them from their home habitats. In the latter case, many people think they are doing the turtles some benefit by picking them up off dangerous roads. They try to relocate them to safer areas, sometimes moving them miles away from their home range or even taking them into different states.

Kids learning about the Piedmont Wildlife Center’s Turtle Connection program surround a Boykin spaniel “turtle dog” that was out on an evidently successful mission to search for box turtles.

Image Credit: Sara Steffen

But Steffen said that the turtles have a mental map and are often very loyal to their original habitat. If they are moved far enough away, they could spend the rest of their lives trying to find their homes.

“Usually they don’t eat or drink before they make it back to their home,” Steffen said. She suggests that rather than moving the turtles to safer areas, it’s best to simply help them across the road.

Aside from citizen scientists, the PWC has other allies: turtle dogs. A few years ago a certain dog owner noticed that his canines had an uncanny obsession with finding the turtles and decided to put them to use with box turtle projects. The PWC and others now use the dogs to track down turtles. Once caught, they fix them up with GPS tracking devices to give researchers a better idea about their ranges.

Steffen isn’t the only person working to get numbers on box turtle populations. Jerry Reynolds, the senior outreach manager at the North Carolina State Museum of Natural Sciences, also has a Neighborhood Box Turtle Watch that calls on people to send in information about box turtles in their area.

“You take some good photographs of the turtle, take good notes of where you found it and when,” he said.

Over time, he hopes that this will give better information about turtle ranges and habits. Steffen said she hopes her program will go on for a century, and while Reynolds said he hasn’t received a lot of data from citizen scientists, he still gets a lot of information from people when turtles lay eggs.

“A big part of this is really more educational than getting really good research numbers,” he said.

Header Image:

Researchers attach radio telemetry devices to box turtles as part of an ongoing effort to track the species in North Carolina.

Image Credit: Taylor Tvede